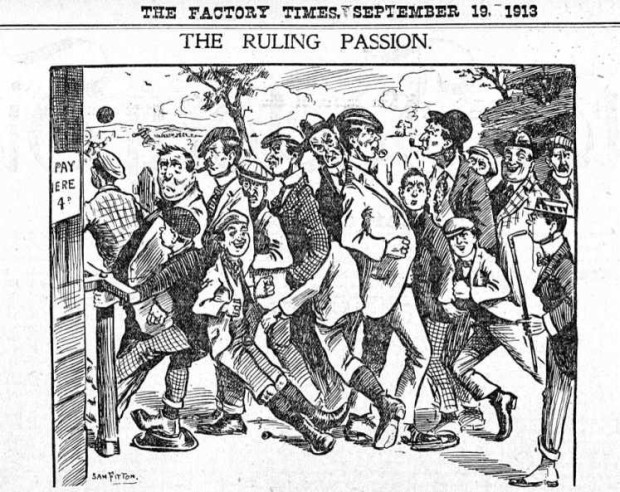

In 1895 the renowned English sportsman (and polymath) Charles Burgess Fry noted that the burgeoning interest in Association football in the North of England was ‘almost a passion.’ Indeed it seemed to Fry that the only way to explain the ‘huge, huge crowds at League matches’ was that the ‘toiling operatives of the Northern towns’ must ‘take a holiday from Saturday morning till Monday night in the football season.’

CB Fry, as he became known, was comparing the meanings and popularity of cricket and of football, and discussing in particular, whether the emerging code of football had overtaken cricket ‘in the popular heart’. While Fry concluded that football was yet to ‘dethrone cricket’, his descriptions of ‘the enormous interest’ in football reveal a sense of intrigue, mistrust and almost bafflement of this new sporting phenomena. Cricket had ‘stood the test of time’, yet here was this young aggressive upstart of a code whose northern proponents were already proclaiming it as the new national game. The phrase ‘almost a passion’ hints at the distaste that many elites of the Victorian age held for displays of emotion, while Fry also disapproved of the partisanship of the crowds who would choose victory over ‘a good match’ and who might take more interest in a League match than an International fixture.

Fry concluded that at least some of the interest in football was the product of a fad – a ‘species of sudden rage’ – as he put it. Perhaps he hoped that the fervent spectator culture of football would diminish like other fads. If so, such hopes were soon disappointed for not only did the zeal for football endure, it spread, transforming the game from a village and school affair into a national and then international form of popular culture with broad social, cultural and economic implications. And soon Fry himself was benefiting from it, first as a writer and later as a professional footballer.

The initial discomfort of figures like Fry – the established middle and upper class, particularly but not only in the south of England – is well known. What has been neglected, however, is the sense that what was occurring in the north around football was novel and absurd. Indeed, one of the things I’ve found so striking in reading British reactions to football in the late 1800s and early 1900s is the surprise expressed by outsiders at the emerging fascination with the game.

Much of this surprise centred around the great meaning supporters ascribed to games of football. When, for instance, the Reverend Joseph Parker journeyed from London to Glasgow in 1887, he looked for religion in the daily papers only to find columns regarding football. ‘He asked if all the world was mad, and all the men and women football players’, before going on to note that ‘he had had seen great excitement manifested at a railway station on Saturday. He asked if the Queen was dead or St Paul’s burned to the ground? No, it was a whole community gone out after football.’

Critics did not only come from the south. Towards the end of 1887 the Lancet published a review that was highly concerned with the physical dangers of football. In response, the Edinburgh Evening News praised the physicality and courage needed to play the game, arguing instead that the main problem was the way ‘a manly game’ was being ‘turned into a nuisance by excessive devotion’, with the consequent ‘football mania’ having a deleterious effect on the character of public lectures and the support of Mechanics institutes and related bodies.

This brief riposte to the Lancet managed to twin what became the two leading metaphors used by critics and supporters alike to describe the culture becoming associated with football: religion and mental pathology. For outsiders it seemed crazy that people were devoting so much time and energy to watching, thinking, dreaming, celebrating and mourning what was merely a game. Insiders acknowledged the absurdity, but delighted in the way a game they were following could seem more important than anything else.

Sometimes the defences of football culture were as revealing as the critiques. After the first game of the 1889-90 football season, the Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette felt compelled to admonish the growing critics of the so-called football mania, who were apparently prophesying that the madness for football would never last:

We already hear the sneerers talking about the ‘football mania’. At the close of the last season these critics indulged in predictions that the ‘madness’ had about run its course, and that in all probability it would suffer from reaction in 1889-90, and then die out, leaving a sense of self-astonishment in the men, women and children who had lost their heads over the ‘absurd pastime’. At the first summons of the season about twelve thousand people declared last night that they were quite as mad as they were last season. And we shall probably find as the months pass, as we found last year, that the sneerers will gradually become mad themselves. We know of several very steady-headed critics of the ‘mania’ who bethought themselves that they would just go and see how utterly foolish the whole thing was. They went, and gradually became afflicted with that lesion of the intellect which they had predicated of others.

One of these sneerers – a well known gentleman – had to offer many apologies in the course of an hour and a half for kicking the shins of spectators near him, the lesion of intellect having progressed so far on a first inspection of the game as to lead him to imagine that he was somehow engaged in the match. Another of the same class, being carried away by the prevailing and very contagious enthusiasm, and having dropped his hat, so forgot himself as to seize the hat of another person in order to wave something when the local team had scored a difficult goal.

Yet while the Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette admitted ‘a certain degree of madness, of British enthusiasm for physical prowess’, it made the intriguing – and now strikingly counter-intuitive – claim that the ‘popular pastime’ of attending games was actually ‘a powerful auxiliary to the temperance reformer’ because this limited the amount of drinking those attending games would otherwise indulge in on a Saturday afternoon. The conclusion was that self-confessed madness had rational benefits:

When one sees ten thousand people with glistening faces at a football match, one feels that such excitements are worthy of praise rather than condemnation. Moreover, the infection of the manly game, spreading to the rising generation, has a beneficial result in the promoting of that physical development which ought to be part of the education of British youth.

By 1891 Durham’s Northern Echo was observing that ‘mania’ for football meant that it was being taken more seriously than politics. Essays and reports on politics would only receive ‘a shrug and a smile of unbelief’ from those of a different political persuasion, the supporters of teams whose play was ‘slated’ would react with much greater vehemence:

Politics, sir. Ain’t in it with football for intensity of partisanship… [political differences might be dismissed with goodwill] not so the choleric supporter of a particular club, not so the spit-fire spectator round the ropes. Say, or write, a word which may be construed as disparagement of his football pats, and the fat is in the fire. You are prejudiced, you are partial, you know as much about football as a cow knows about astronomy, and so on, and so forth.

The ground was already being laid then, for later criticisms of football replacing religion as the ‘opium of the masses’. A number of Christian ministers felt threatened by the fervor for the game. As the Reverend John McNeill noted in 1892, many ministers were ‘groaning and lamenting at the “eternal fitba”’ because not only did whole communities seem to go to the game:

They had to talk it over again, and if it had ended there it would not so much matter. But it did not. On Sunday they were as much possessed as ever; they stood at street corners and took a walk in the country and talked the whole match over – every kick being kicked again, and every man’s merits being canvassed.

In 1896, John Thorpe, Rector of Walcot, even had a go at reversing the metaphor, arguing that Christianity was ‘the greater sport’, and pleading with his audience to exercise ‘a little’ of their enthusiasm towards sport to religion as well. By this time the beginning of each football season would be preceded by a flurry of reports of mounting excitement and hope all around the country that the beloved teams of various football supporters had recruited and trained well and were now set to play gloriously and win at least one significant trophy. In other words, a key characteristic of the seasonal life of football – the religious-like promise of a new season untainted by what had come before it – was already in place.

In 1902 CB Fry played for Southampton against Sheffield United in the FA Cup final in front of more than 76,000 spectators, many of whom had ‘invaded London’ from the north. Fry had reportedly become a professional footballer to enhance his prospects of being selected for England for football along with cricket. In the previous year he had achieved that aim, playing against Ireland and Canada in front of a combined crowd of less than 10,000. The culture of football was still more localised than cricket where the international test matches garnered more attention than other contests. Yet the affection towards football ‘in the popular heart’ was continuing to grow.

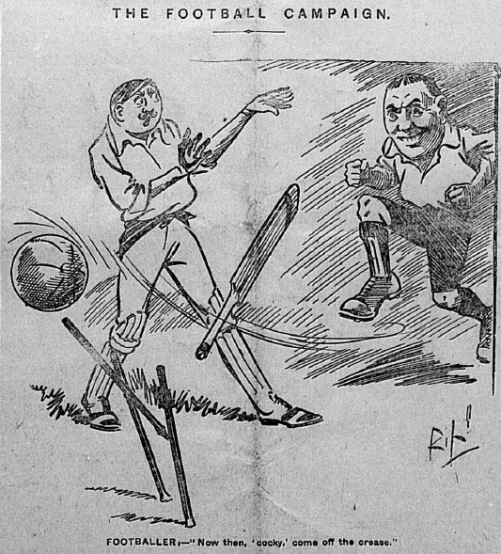

The Athletic News had marked the turn to the 1901/02 football season with a cartoon of a football knocking over the stumps of a dismayed cricketer. Over the next decade variations of this cartoon would frequently herald the beginning of football, whereas no such cartoons celebrated cricket. But rather than focus on the battle between cricket and football, I think it is worth instead exploring how the ‘rational’ Victorian era gave birth to an enduring culture of absurd, excessive and strangely pleasurable devotion to the sport of football.

Matthew Klugman researches and teaches in the history of sport at Victoria University where he focusses, among other things, on those who love and hate sport. He is currently studying the emergence of modern spectator sport cultures in Melbourne, Manchester and Boston. This research project is supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Fellowship (project number: DE 130100121).