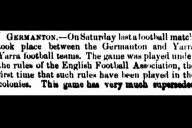

An underground freeway is being built on the eastern edge of Maastricht. The current site is a broad expanse of dust. Middle of the range sedans and trucks speed along the four lane, two-way road. There are as good as no pedestrians about. It is a mild evening, one of the first of spring, and those enjoying their recreation are on the other side of the train station, closer to the river, walking about, eating, drinking, enjoying life in the centre of Maastricht.

This small city is at the base of The Netherlands. It is surrounded by hills and there are no canals. While walking, running or cycling around the town, one moves back and forth into Belgium; passing walkers greet one another in French rather than Dutch. Car numberplates change from NL to B.

At the end of the street, a banner advertises the Tuna Festival, a local music festival dedicated to Iberian music. On the bridge that crosses the Maas River, an elderly man endlessly repeats a brief series of notes on a fragile recorder. Some kind of melody. A hat below ostensibly placed for receiving coins. A young woman poses, lying down and brushing her hair back in the late afternoon sun. On the other side of the bridge, a couple of guys inadvertently watch. Spanish musicians, dressed in black costumes and carrying acoustic guitars over their shoulders, walk in groups, on their way to performing in the festival.

The glow of the Golden Arches

Stadion de Geusselt is virtually anonymous in the surrounding landscape. The stadium is in a ‘business park’ and is part of the office infrastructure. Next to the stadium is a McDonald’s, and the Golden Arches loom over the southern end of the stadium throughout the game. Now and then the arches are lit; for much of the second half, the arches remain in the dark.

The surrounding street names are clearly themed, indicating the newness of the area: Stadionweg, Olympiaweg and P.de Coubertinweg. MVV Maastricht’s fans cheer ironically when the Arches are finally lit up towards the end of the game. The grandeur of the evocation of the Olympics and its founder resonates discordantly with the modest facilities.

The stadium, built in 1961 and renovated in 2002 is ‘an all-seater’ with a capacity of 10,000. At best, it is charmless. There is little romance in its multi-purpose functionality, its small size, and the walkway and large fence that runs along the perimeter. The walkway and fence makes the crowd easier to police.

The colour of the blossoming trees offers a brief respite from the greyness of the environment. Brown-wooden boxes with lonely occupants sell tickets to the few who arrive. Two men are selling MVV paraphernalia from a merchandise stall. One item is a retro replica shirt produced by the Amsterdam-based football-fashion company, Copa. Somehow the hipster coolness of Copa seems out of place in these surroundings. The only shirts that remain are shiny XXL shirts, seemingly based on a 1980s or 1970s shirt. There is little interest, but a few fans take the free match-day programs sitting inside the booth’s window.

Inside the stadium, merchandise is being sold from small tables. There are the usual goods such as scarves and shirts, but as my brother, Thomas, points out, there is also liquid soap. Lather up with MVV.

Security is tight. There are no queues and the crowd that dribbles in through the entrances scan their tickets on digital barcode readers. Large men in red jackets frisk the hooligans-in-waiting as they enter the stadium. Plastic bottles and hand sanitizer are designated as possible weapons and confiscated. A digital camera is not; even though it would make a fine projectile, it is presumed that the hooligan wouldn’t throw it at a player or referee. Tickets permit crowd members to enter a particular section of the stadium, roughly two blocks of seats per ticket.

MVV’s ultras congregate at the south-western end of the stadium. A large, muscular man in a white Fred Perry polo surveys the crowd as they pass through security. Other MVV ultras queue at the makeshift bar. Beer and fast food are bought with tokens. A unique currency for each venue it seems. Perhaps this is the norm in football stadiums elsewhere in Europe, or maybe just in The Netherlands. Whatever the case, it slows down the act of purchasing and obfuscates the price. Small and large cups are being sold at one or two coins, the coins, being priced at two euros each. And thus, a plastic cup of sparkling mineral water is two euros. The stadium is under 40% full; the management must be hoping they got their fill of beer and sparkling mineral water.

‘Football is not mainstream in Maastricht’

I am at the game with my brother, who has been living mainly in The Netherlands since about 2010. When in The Netherlands he has lived in Maastricht. He is ambivalent about the town, but likes the country. This is his first MVV game and he says he doesn’t think any of his Maastricht-based friends would be interested in coming to the game. My friends in Leiden, too, have scoffed at my interest in going to a Jupiler League (i.e. second tier) game. It seems there is some condescension towards football watching, especially if it’s not at the highest level.

Indeed, inside the stadium, the mood and style is decidedly low-key. The outward appearances contrast significantly with the well-to-do chic and bourgeois charm of Maastricht’s cobblestone streets. A few in the stadium are dressed smartly – the youngish MVV bureaucracy – some caked in makeup – none other than the players’ wives and girlfriends. Football is not mainstream in Maastricht. Sitting in the sterile, uniform stadium watching a mediocre football team loses out to sitting on terraces by the river in the late afternoon sun.

But today might be an exception. The MVV Ultras, indeed, they don’t seem to have adopted a more specific name, are up-and-about from the get-go. Their capo, in black polo, gesticulates wildly; the main movements being arms spread wide and then raising them up and down before starting a rhythmic clap. His choir is a group of fifty or so burly youths; his drummer beats an angry rhythm. My brother points to the unfortunate absence of brass instruments for which Maastricht is known. The town is steeped in music tradition and is the hometown of that modern giant of pop classical, Andre Rieu.

MVV opens the scoring – a surprise given their lower position. And this is met with rapturous applause and cheering. It was the result of a miscommunication in defence and one of FC Volendam’s players was caught on the ball. Within a minute FC Volendam equalise. The cliché in this case seems to hold, ‘you are most vulnerable after just having scored’.

The first half ends 1:1. We are relieved to have seen some goals; a little action. Thomas and I presume the game will end with one or two more goals at the most and that FC Volendam will win; they are, after all, fourth on the table compared to MVV’s 14th. But what happens in the second half is unexpected.

Here’s an edited version of Google Translate’s entertaining match summary from MVV’s website:

Mince meat made of FC Volendam. The normally so difficult to defeat opponent was mainly in the second half dismembered by the team of coach Ron Elsen. Stef Peeters (2 times), Bryan Smeets, Davy Brouwers, Pascal Huser and best player Leroy Labylle managed to find the net behind goalie Black Hat [Yup; Google even translates surnames]. One blemish on the win was the failure of striker Sven Vomiting. He broke his nose in a rash action of a FC Volendam defender. MVV Maastricht set again for an offensive. It was a shooting gallery with gusts through the middle of Black Hat, but nobody knew in the first half to score. […] In the second half on the other hand it was just found it. Although not immediately, but after about 20 minutes the party started: A fantastic individual action of Leroy Labylle led to the 2-1 of the left back. Moments later Jordy Croux went in the right direction box. With a substantial body check the little winger was halted. Penalty, referee Gerritsen decided rigorous. Stef Peeters put in for his first of the night and left Black Hat chance. An unprecedented discharge followed, both on and off the field. It made for an atmosphere that the Star Carriers to high altitude floated. Again Leroy Labylle was that thundered on the left and this time the gloves of Black Hat ravaged. Pascal Huser was attentive to the recoiling ball: 4-1. A few minutes later ensued scenario again: Labylle steamed on to the left of the goal line and was nothing and no one to stop. He kept the list and reached Davy Brouwers saw, however, turned his handsome bet by Black Hat. After 80 minutes, there was also the poor Volendam goalie no stopping him. Davy Brouwers made to assist from Leroy Labylle his 15th goal of the season. Seven minutes later led a gala performance (heel Niels Vorthoren) to a handsome goal of Stef Peeters, who controlled the ball 25 yards into the far corner chased: 6-1. The goal of Overtoom, deep into injury time, was only for the statistics: 6-2.

On the margins of Maastricht

The game ends just before 10pm. Back at Maastricht station, the convenience stores have closed and I need to rely on vending machines for the stomach entertainment of a crunchy Kit Kat bar and another two euro dose of water for the three-hour train ride north to South Holland. The pre-game ritual of beer (alcoholfrei) and chicken kebap (a little too heavy on the sodium) seems like a long time ago; prior to the quietness of the pre-game stadium atmosphere and prior to the explosion of football euphoria Maastreech-style.

The train station serves as the dividing line between the centre and the margins of Maastricht, between the pleasant and that-which-is-to-be-kept-out-of-the-way. The streets around the stadium are wide, quiet and of uniform age. They reek of planning, rather than improvisation. The stadium is an antithesis of Maastricht’s genteelness; the slowly building raucous celebration a counter to the appreciation of the Spanish guitar concerts taking place on the other side of the river.

Andy Fuller writes on football and urban culture. He lives in Leiden, The Netherlands. His website is readingsideways.net