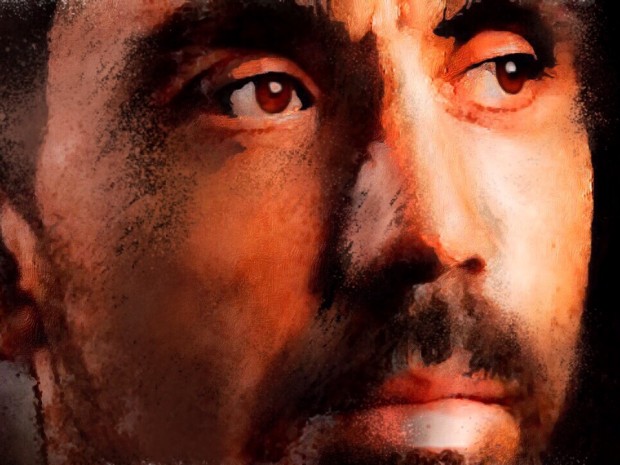

And so Adam Goodes will make his return to the Swans in their game against Geelong this weekend. Football might return to being about the result. Goodes might simply be a footballer, one of 36 on the field, doing his best for his team for those two hours.

His return has been ushered in after a weekend celebrating his contribution to the game and acknowledging the importance of reconciliation. Teams and individual players did their best to prove that they supported Goodes. Richmond’s banner stated broadly, ‘we stand for reconciliation’, and the team – as the Western Bulldogs did, too – played in their Indigenous jumper. Melbourne players wore the colours of the Aboriginal flag on their wrists. Lewis Jetta of Sydney and Danyle Pearce of Fremantle cut through the noise of commentary with their clearly articulated goal celebrations, which drew on their Indigenous culture.

And of course, some people, like Eddie McGuire, still didn’t get it: “Let’s not dehumanise people. This is the game of football. This is what humanises people. This is what exalts people like (AFL Legend) Ron Barassi so that with his legacy he becomes a giant in our community that we can learn from.” In his curious mixture of narratives, he couldn’t bring himself to admit his own sorry role in the dehumanisation of Goodes.

Goodes himself has stated he has been humbled by the support he received over the weekend. Perhaps us footy fans are getting off lightly, that he has come back so quickly, and that all has seemingly been forgiven.

The Boo Agenda

Goodes has captained the Sydney Swans, been part of two premiership teams and won two Brownlow Medals (2003 and 2006). He has played some 360 games – and is currently playing what most consider to be his last season in a team that is once again bound for a top four finish. Goodes, along with players such as Michael O’Loughlin, Brett Kirk and others have been credited with reviving the Swans as a club since the early-2000s and helping to create a much venerated and respected winning club culture. The Swans are renowned for their ‘leadership’ qualities and their ability to win against expectation. Almost yearly, they defy experts who predict them to finally be on the slide.

For the past decade, the Swans have been able to mesh big-name recruits with cast-offs from other clubs. Led by coach Paul Roos during the first decade of the 2000s, the Swans created a culture which focused on each player ‘playing their role’; so that there would be an equal level of performance across the team. Despite the presence of many very skilled players (such as Goodes) the Swans expected each player to perform well; it was this consistency that helped them to their 2005 and 2012 premierships. Moreover, the club was able to successfully negotiate a transition from one coach – Paul Roos – to the next – John Longmire – with a minimum of fuss. Such a smooth transition, and the club’s consistent performance over more than a decade, indicates the professionalism with which the club is managed.

In short, the 2014 Australian of the Year has been one of the most successful individual players of the modern era in one of the more successful clubs of the last 15 years. His positions on certain social issues and his interventions have sometimes been controversial. The attitude of AFL crowd towards him has become polarised throughout the 2015 season, with the increase in occasions that Goodes is booed by opposition fans. This was most noticeable when he was booed by sections of the Hawthorn crowd in Round 8 (23rd May), the booing was then taken up by fans of other teams in the following weeks. As a means to counter the booing, Swans fans took up the habit of applauding Goodes every time he gathered the ball (regardless of whether or not he did so in a spectacular manner). Coaches and players made public statements requesting their own fans not to boo Goodes.

The ‘Ape’ Racist Abuse

Goodes was the target of a racist slur – ‘ape’ – during a game between Sydney and Collingwood at the MCG on 24th May 2013. The game took place during the so-called Indigenous Round: a round of football in which the contributions of Aboriginal footballers to our (white Australian) game of footy is specifically acknowledged. Even if the politics of the Indigenous Round are a little uncritical, it is a themed round that is wholly supported by Aboriginal players playing in the AFL. Goodes responded to the racial vilification by directly pointing to the person who racially abused him. It emerged that the person who directed the racist abuse at Goodes was a 13-year old girl, coming from a relatively poor economic background. Her lack of awareness about her actions and her lack of education was a part of the discourse that led to her being positioned as the victim of some kind of bullying by the adult and famous Adam Goodes.

The day after the incident Goodes gave a 15 minute press conference in Sydney, patiently explaining why he was hurt by the statement and why it didn’t matter that the person who made the call was still a child. In the same press conference he called for people to support the girl and educate her so she would know why her words (and point of view) were so offensive. He called for those close to her (and others) to ‘get around her’ [and provide her with comfort].

On the following Monday (the game was held on a Saturday, Goodes’s conference was on the Sunday morning), Eddie McGuire, a prominent media personality and president of the Collingwood Football Club, suggested – live on air – that Adam Goodes should be invited down from Sydney to come and help with the promotion of the recently released King Kong, ‘you know with the whole ape thing and that’. His racist comment, and by extension endorsement of the 13-year old girl’s racist abuse, was dead-batted by co-host Luke Darcy, who simply said, ‘no I don’t think it would be a good idea’, while trying not to let on his shock at McGuire’s comments, and denying the presence of anything humorous in his statement.

Goodes did not accept McGuire’s obsequious apologies over the coming days. The McGuire-Goodes incident was one of many points of conflict between the Swans and Magpies, but, this one was clearly the most personal; the other conflicts between the two clubs always having a touch of jousting between two big clubs from rival states.

Goodes sent a tweet stating ‘two days after being called an ape and this is what I wake up to’. During the day of the incident and the following days, McGuire used his ample opportunities to grovel and state that ‘it was a slip of the tongue’ and that it was not indicative of the type of person he really is. He claims to have offered his resignation as president – perfunctory at best – but that he was discouraged to do so by legendary Aboriginal footballer Michael Long. Nonetheless, McGuire continued to occupy public media attention; while Goodes, understandably, sought to escape the media limelight.

These two incidents in which Goodes became an unwilling yet critical participant show how some things have changed regarding ‘racism’ in footy, while other things stay the same.

Firstly, Goodes pointed out an individual racist abuser during a game; after which he took himself from the field – presumably on the basis of his belief that he should not have to put up with it. Following this though, Goodes became the villain of the incident for victimising the young girl who was framed as ‘vulnerable’ and ‘naive’.

The second incident shows that being a ‘good bloke’ always trumps the making of racist comments. And that those who choose to focus on the racist comments are obsessive about trivial details and refuse to see the broader picture of what ‘the bloke is about’.

In both cases, the critical countering of racism is trivialised and its victims are further blamed for disturbing the good feelings we seek to maintain about ourselves.

What’s behind the abuse?

The 2015 season saw a continuation in the booing of Goodes. This was initially highlighted after the Hawthorn-Swans game. Journalist Caroline Wilson, speaking on Offsiders, suggested that it may be a result of the specific rivalry between the two clubs, but she also stated that the abuse was unworthy of a champion of Australian Rules.

With each game Sydney played in Melbourne, Goodes continued to be booed; on the other hand, in home games, he would be specifically applauded whenever he took possession of the ball. Goodes gave mixed messages about how he was dealing with this boorish practice: he said it motivated him to play better and at other times he said he ignored it. With his career coming to an end – most likely at the end of this season – he played a couple of games in the reserves team for Sydney. This not only enabled him to recapture his good form, but, it was perhaps also a means to escape media attention and the racist abuse – articulated through booing – from hostile crowds.

Footy pundits have debated whether or not the booing has been racially motivated. Many have claimed that booing is a part of crowd behaviour at the footy and always has been. Many have also claimed that players such as Liberatore, Lloyd, and Langdon had been booed and that wasn’t racially motivated (because they’re white), so, why should it be with Goodes

This is the playing of the ‘colour blind’ card: one should have the right to boo anyone, regardless of his race, religion, whatever. As if, issues of identity aren’t of any consequence in determining who one is prejudiced against.

Goodes’s character was also questioned. He was described as a sook, someone who played for free-kicks and someone who was a dirty player. And as such, Goodes was similar to most other players in the competition. He had been reported and suspended at times, but he was far from being a regular at the tribunal.

And at the same time, those who boo Goodes have found it particularly difficult to articulate why he is booed. The answer is that it is from a racist motivation; exactly what they don’t want to admit. All of Goodes’s achievements didn’t matter a jot in the face of his trivial misdemeanours and his dubious attempts at character assassination. He is most likely the first ‘Australian of the Year’ to be routinely abused in such a boorish, racist and humiliating manner. The idea of a player who could be an activist too was not tolerated either.

Goodes had remained coy about how the booing was or wasn’t affecting him. He seemed to be uncertain how to respond, or whether to respond. But, when he did respond, it was proudly and unequivocally. He replied to the aural racism, boorishly articulated through the un-nuanced drone of booing, with a five second dance move directed to the pocket where Carlton supporters were sitting in the ANZ (Olympic) Stadium in Homebush, Sydney. Although the number of Carlton supporters was small, there was enough for the booing to be audible in the stadium’s broad expanse.

The television coverage caught Goodes’s celebration live and the two main commentators – Bruce McAvaney and Dennis Cometti – responded awkwardly. Cometti stated with a loaded and patronising comment: ‘best not to do it – still none of my business […] won’t stop the booing though, will it?’, while McAvaney went in search of a more neutral statement, simply saying, ‘good stuff there’ – as if somewhat unsure about what was happening. The replay captured the expressions and gestures of the crowd as Goodes danced towards them. Some looked surprised, some gave him the thumbs down, some made crying gestures at him and some were non-plussed.

At the game’s conclusion, Goodes was interviewed and he was asked about the celebration. He said that it was ‘nothing untoward’ – perhaps meaning provocative or insulting. He said that it was a dance he learned from the Flying Boomerangs, an Aboriginal youth football team.

In the following days, Eddie McGuire – he of the King Kong racist allusion to Goodes – trivialised the dance by calling it ‘a made-up dance’ and that Goodes should have warned the crowd first before doing it. Dermott Brereton, a confessed racist abuser of players such as West Coast Eagles’ Chris Lewis and St.Kilda’s Nicky Winmar – called the dance ‘quite violent’. Brereton would know about violence: after all he spent more than 20 weeks of his career suspended.

After playing a few more games at home, and some in Melbourne and Adelaide, the issue had relatively died down, even if the booing hadn’t stopped. Media attention, however, was once again drawn to the booing of Goodes after a teammate of his, Lewis Jetta (from Western Australia), performed a similar dance. Jetta’s celebration was perhaps not as accomplished as Goodes’s, but, it contained the same basic steps, as well as the most ‘provocative’ (well, for some) element: the throwing of an imaginary spear. Jetta, a quiet spoken man, of elite athletic ability, said after the game that he had ‘had enough of the abuse of Goodes’ and that he was ‘standing up’ for his mate. Goodes stood alongside him during the press conference.

Footy contest

Goodes’s dance, also referred to as a ‘war cry’ was a progression of earlier gestures made by Aboriginal footballers.

During the 1980s, the legendary brothers Phil and Jimmy Krakouer responded to the boos and racism of crowds by deploying their exceptional skills and subsequently ignoring the adulation of both teammates and crowd. Their play was more than about beating an opposition.

In 1993, Nicky Winmar gestured to his black skin at the conclusion of a game in which his team had emerged victorious – providing Australian Rules with its most striking ‘black power’ moment.

Goodes – circa 2013 – gestured in a reporting manner, identifying a perpetrator of racism. Goodes – circa 2015 – embodied his Aboriginal identity through performing a brief dance with cultural resonance to Aboriginal Australians. Jetta appropriated this dance for himself; claiming it as both his own and as a means of solidarity with Goodes.

The field of Australian Rules football games has shifted from being a safe place in which white Australians can watch the exotic black natives perform their footballing skills, to being a site in which Aboriginal Australian footballers explicitly show their pride in their identity above all else.

The actions of Goodes – and by extension, Jetta’s – have ushered in a new era where ‘going to the footy’ is no longer a safe, sterile and circumscribed part of everyday life. Instead, the football field has become a site of contestation, transgression and pride.

Andy Fuller writes on football and urban culture. He lives in Leiden, The Netherlands. His website is readingsideways.net

Shoot Farken wishes to thank Jeff Vatuvei @AardigOranje for the digital illustration of Adam Goodes.