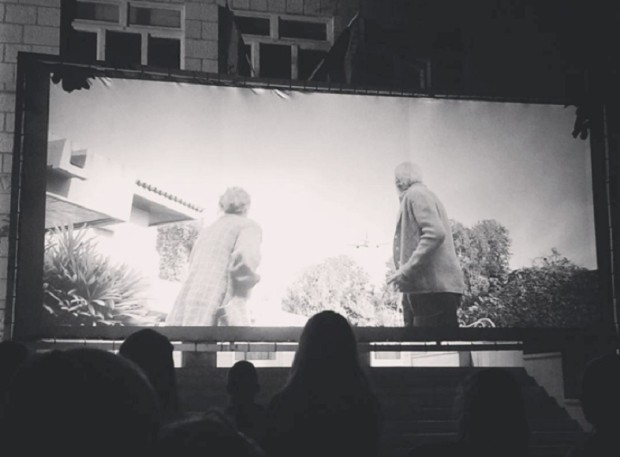

There’s a scene near the end of Be Kind Rewind, when Jerry and Mike’s film is shown on the projector, and it’s interspersed with cuts to the small community who frequented the video store.

As the glow from the screen reflected on their faces, the wonder in their eyes cast just as moving a picture.

The light flickers from the projector and the various reactions of glee from the small audience in the shop, despite Be Kind Rewind’s precarious situation, suggest film can transcend time and circumstance.

While indicative of Michel Gondry’s more inviting tone in this particular film, in that scene, we as an audience are reminded just why we watch film and what motivates us to do so.

I had only just arrived in my father’s home town of Posušje a few days beforehand, but I never thought that there, I would witness a similar picture in the flesh.

Any child of migrants can attest, the stories of days in the homeland are generally told through rose-tinted glasses, only for the individual to realise later in life the untenable hardships that led to departure.

Located ten kilometres from Imotski, right on the Cro-BiH border, Posušje is grim, despite the stunning and ever-present nature on display.

Hovering between 40-45% unemployment, and judging by the town’s infrastructure, the state of affairs is stark and reflected in the recent 4% decrease in population, with Croatian nationals seeking greater opportunity across the European Union.

Boarded-up shop fronts in the centre accompany general desolation, in a town where the only entities that prosper aside from the church are Kafici i kladionice (cafes and betting shops).

I’ve mulled over this point a number of times, trying in vain to come up with a way that would not make me sound like an arrogant prick, but this was the last place I expected to watch avant-garde film.

In co-ordination with the Sarajevo Film Festival, which opens this Friday, Udruga PAUK (Posušje’s Activists for Art and Culture) organised open-air showings over two nights of Damian Szifron’s Relatos Salvajes and Roy Andersson’s A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence.

I only found out about it a day beforehand, spotting a flyer on a morning walk.

In just its second year, on face value, the event holds benefits for both parties. For SFF, it’s a direct promotion of the festival locally.

Meanwhile for Udruga PAUK, it provides locals with an accessible channel for international film, and an extension of the group’s objective to promote art and culture within the town.

Ena Rahelic, SFF Head of Sales, echoed that sentiment.

“It’s definitely a good way for us not only to promote the festival in the lead-up, but also to give inspiration to locals throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina interested in film,” she said.

“In principle, we as an organisation have a responsibility to the local industry, and this helps in achieving that.”

Personally, I was excited for a couple of reasons. Firstly, I hadn’t been able to watch either movie until that point. Now I’ll get to watch them, under the stars at the local school in my old man’s birthplace, of all the places on this Earth. Far out.

Secondly, and just as important, I was keen to see how the occasion and films themselves would be received.

One of the editors at Shoot Farken said to me this week, “watching films in other countries with different audiences is a wonderful experience, as good as going to the football.”

While in agreement, I believe it’s equally if not more insightful, especially within this context.

With football, you can learn of a nation’s values and customs. However, with film, sitting in that audience, one can directly unveil their traits and eccentricities, as well as general sense of humour and perspective.

The disparity in reactions to the two films could not have more clearly reinforced this point to me.

Relatos Salvajes won the audience award at last year’s Sarajevo Film Festival, and with this cultural framing in mind, I could see why.

The acceleration of anxiety and angst, with an almost carnal desire for revenge linking the collection of shorts, is quintessentially Argentine.

Such a highly concentrated mix of cynicism and absurdist humour, however, will always be appreciated in these parts.

While laughs were hearty and continuous, it was during Las Ratas, the story of an ex-con turned parliamentary candidate stopping for a potentially fatal bite to eat, that my perceptions on this point manifested before me.

While the kids in the front couldn’t contain their laughter at what was on screen, there was a palpable sense of despair in the back with their parents, no strangers themselves to institutional corruption.

A harrowing silence washed over them, only for a moment, and I needed to step to the side for a cigarette.

It was here I met Franka Vican, President of Udruga PAUK, who noticed I wasn’t from around. Must have been the trainers. Shit, I don’t know.

After exchanging pleasantries and compliments, we organised to speak on the event after the second film.

Deadpan in delivery and seemingly random yet hilarious and meticulously thought-out, Andersson’s effort was received completely differently to Szifron’s.

The fixed-camera shooting prevalent in the conclusion to the Swedish director’s existential trilogy captivatingly draws the viewer in, alternately reflecting society’s gradual descent through its colonial past and materialistic existence.

The Golden Lion winner, however, bored the audience, who mostly walked off after half an hour.

Every now and then during the film, someone would walk past, decide to sit down, kill a butt and chat on the phone; but by the end, only a handful remained.

Vican herself admitted it was an effort to watch, but ultimately rewarding.

“We had a good idea there would be a difference between the two nights. At this stage, our audience simply doesn’t have the patience or understanding yet,” she said.

“At times I found myself struggling to watch tonight, but eventually it was worthwhile, and I’m thankful to those who decided to stay.”

Asked whether there were other factors at play in the fallout, Vican agreed.

“We’ve only been putting on these kinds of events for about a year now, but currently, it’s mostly going to be parents bringing their kids just to get out of the house.

“There isn’t much on offer in Posušje, and that’s why we created the group, to try and provide the township with something they haven’t been subjected to.

“Hopefully over time, it’s something that can flourish.”

While there remains a cinema in the town, or Kino dvorana, it’s pretty clear an appreciation of film is lacking.

It struck me over the two nights that for many it was similar to a consumer exercise, where the public came expecting to be entertained.

Irrespective of whether this is some petty petit bourgeois gripe on my part, this kind of thing in West Herzegovina is nevertheless in a stage of infancy.

I realised, that aside from appreciating film in this instance, it should be that which I appreciate most.