When we write about people, we talk about the times that shaped them and the experiences they’ve had. How else do we begin to understand these complex figures — especially those who’ve lived through eras we haven’t?

Time is everything, and to give context to that time is important. The decisions and paths we take in life are governed by the social forces and constraints of that period. Without examining history, we can never truly understand who we are.

Great figures like Muhammad Ali are no different. And in the week that has seen “The Greatest Of All Time” pass, there have been a raft of tributes and homages about his life and significance.

Some have focussed on how the affection toward him grew after his ability to speak began to diminish; others spoke about how analysis of him “transcending race” was flawed, and many spoke about how we now “sanitise” Ali as a figure.

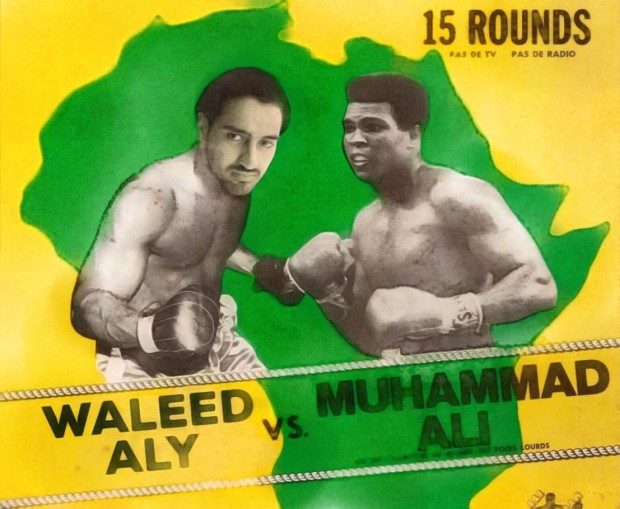

Waleed Aly penned the latter. The sentiment is true: we have sanitised Ali, who was a radical figure in America at a time when African-Americans weren’t suppose to be.

The premise of the piece is correct — Aly explains that Muhammad Ali “was also frequently radical in a way so many of those now celebrating him would detest…” — but the piece fails to understand that very radicalism.

When referencing Ali’s political birth within the Nation of Islam — which at the time preached separatism — Aly makes the unfortunate claim that it was “an avowedly black supremacist group.”

Aly continues: “Even the black press was uneasy, concerned that his separatist stance undermined the civil rights movement’s fight against segregation.”

Whether or not you agree with Ali’s stance then on separatism, you have to understand where that comes from. Ali was a product of the deep South, growing up in Lousiville, Kentucky, in a time where segregation and brutality against Black people was the norm. He recounted a story to Michael Parkinson of trying to order a meal in his home town:

I had a big medal on, and in the restaurants at the time, black folks couldn’t eat downtown. And I went downtown, I sat down, and I said, ‘A cup of coffee and a hot dog.’ The lady said ‘we don’t serve Negroes’, I was so mad I said, ‘I don’t eat them either, just give me a cup of coffee and a hot dog!’ I said, ‘I’m the Olympic gold medal winner. Three days ago I fought for this country in Rome, I won the gold medal and I’m going to eat.’ I heard her telling the manager. Anyway, I didn’t raise nothing, they put me out. And I had to leave that restaurant in my home town where I went to Church and served in their Christianity and fought in all the wars. I just won the gold medal and I couldn’t eat downtown. I said, ‘Something’s wrong.’ And from then on I’ve been a Muslim.

(Parky’s People, Hodder & Stoughton; 2010)

He was proud. But he was shunned in his town, a place he grew up his whole life. How hurtful must that feel, to not belong in the place you call home.

So Ali didn’t wake up one day and decide upon segregation. It was something imposed onto him.

Waleed Aly’s discussion of the Nation of Islam’s alleged “black supremacy” lacks context: “But exactly who among today’s media would cop to admiration for Ali’s belief at the time that white people were devils who should be kept entirely separate from blacks?”

This frames Ali as a sort of cartoonish “black KKK” figure, which is completely ahistorical. This was an America where black people weren’t supreme,economically or socially, where public lynchings of black people was not an uncommon pastime, where vocal African-American figures like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jnr. were shot and killed.

This was a time in history when African-Americans weren’t given basic civil rights. So forgive me if I don’t judge someone from a period where trauma was so prevalent for calling white people “devils”.

Aly’s criticism of Ali’s “devils” comment extends to questioning the way he framed his opposition to the Vietnam war, which is perhaps most disappointing: “Even his heroic objection to the Vietnam draft he cloaked in uncomfortable terms: ‘My enemy is the white people, not the Vietcong’.”

Sure, the terms are uncomfortable — but they are rooted in truth. Black Americans were marching, protesting and trying to demand their rights from a deeply racist establishment. That establishment was white, so for Ali to draw the conclusion that those who withheld his rights were his enemy doesn’t seem unreasonable. Why would he fight and kill for that same establishment that withheld so much from him?

One of Ali’s most famous speeches: “No Viet Cong, called me a nigger.”

One of the biggest aspects of Ali’s identity was the fact he was Muslim — changing his name was the most obvious expression of this transformation.

And Islam is a broad spectrum with many different sects and ways of worship depending which part of the world you live in.

So the terms in which Aly describes the Nation of Islam seem slightly patronising: “Because although he left all that [Nation Of Islam] behind and entered Islam proper, I can’t deny that so much of his greatness and significance was forged in the fires of that ‘struggle in the dark’.”

What is “Islam proper” as Aly points out? Well ask a Sunni, Wahabi, Sufi, Salafi, Shi’a and so on, they’ll all give you different answers.

Like Malcolm X’s journey, it is perhaps not constructive or meaningful to understand Ali’s roots in the Nation Of Islam in opposition to orthodox Islam as much as they were a path to it. And whatever you think or feel about the Nation of Islam, they laid the foundations of the story of Islam in America at a time when Islam was very much unknown.

The Nation’s ideology was an avenue for Black Americans to reclaim their past. To reconnect to their fractured identity after years of slavery and torture, and all the trauma and pain that came with it. I cannot imagine how that process would feel like, living in a time when people were so thoroughly dehumanised.

For Aly to say that Muhammad Ali’s “words failed as an ideology, but worked as a symbol of pride for a humiliated people” misunderstands that this was indeed their express ideological purpose.

Ali was a rhetorical genius who knew exactly what he was doing for the pride and self-esteem of Black and colonised people worldwide. Ali may have later denounced what the Nation of Islam was and sought other forms of Islam, but that doesn’t take away the impact they had on Black Muslims and Black History when Islam was invisible in America.

Aly seems to suggest that Muhammad Ali is worth remembering for his courage and conviction rather than the content of his ideas: “If he’s the greatest, it’s because he so relentlessly (if sometimes dubiously) challenged the world he was in.”

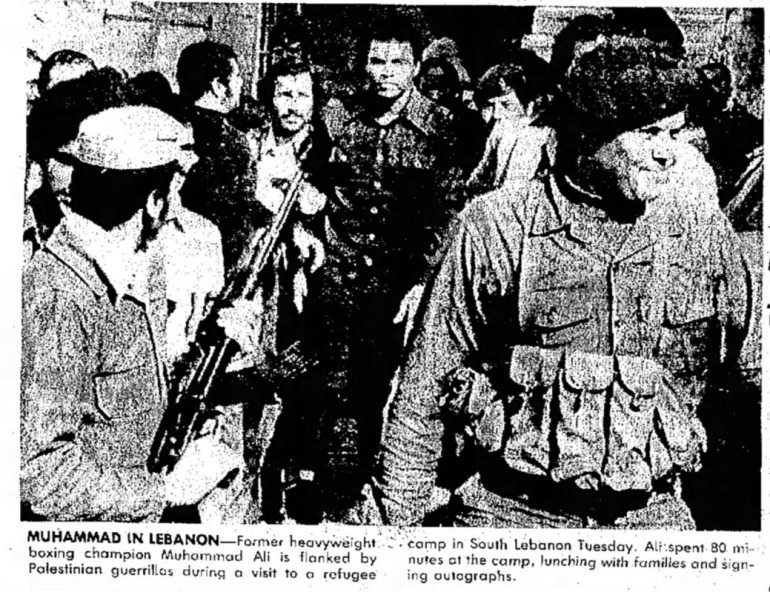

To limit Ali to his brash attitude and quick wit is to lose the substance of the man. Surely to many of us he’s the greatest for what he stood for, whether that be visiting the inner Melbourne suburb of Fitzroy to meet Indigenous Australians or a dusty refugee camp in Lebanon to give support to Palestinians, Ali created solidarity with marginalised people from all walks of life.

Source: The Gaston Gazette (North Carolina), Mar 7 1974.

However, there’s one sentiment in Aly’s piece I can agree with: “He deserves more than for us to remember him by forgetting who he really was.”

Rest in power Muhammad Ali.

Ahmed Yussuf is a Melbourne based journalist and founder of race and politics podcast Race Card.

Nice. You were much more polite than me, but then again, I know the method by which Aly operates.

Thank you for your piece.

RIP brother Muhammad Rahmat Allah 3Layk