A rag-tag bunch of semi-professionals led by a street-wise war orphan arrived in West Germany 40 years ago to take on the football world’s elite. And so was born the legend of the Socceroos.

“Why have we got these kangaroos at the World Cup? How have we ended up with this bunch of no-hopers at the world’s greatest tournament?” – Bild-Zeitung newspaper, 1974

Well, what did the Germans know? But this was the common view held not only by the Germans but most of the football world at the time – and who could blame them?

In 1974, the World Cup was still a very different beast compared to the hypercommercial quadrennial mega-event that is broadcast and consumed by an insatiable public the world over; back then it was more like a teenage Arnold Schwarzenegger who had just discovered the gym.

Crashing the party

It was still a mainly European/South American jamboree with a few exotic, scruffy gatecrashers from the wrong sides of the global village begrudgingly allowed in to the annoyance of the football purists. It was also a damned sight harder to qualify than today. Even England, the 1966 World Cup champions, didn’t make it to West Germany, knocked out by a super Polish team that eventually finished 3rd ahead of Brazil.

Of the 16 teams in the 1974 tournament, only one country from Africa, CONCACAF and Asia/Oceania was given the chance to qualify. The three countries made for a curious trio. Two went on to become among the most unfortunate countries in the world while the other has remained the ‘lucky country’.

Zaire was the first black African nation to ever qualify for the World Cup. The Leopards had become an African football power, winning the African Cup of Nations in 1968, qualifying for the World Cup in 1973 and then winning the Cup of Nations again in 1974 en route to Germany. Zaire also made the global spotlight in 1974 when it hosted ‘The Rumble in the Jungle’ Ali v Foreman fight. The second-largest country in Africa, now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo, then fell into ruin after dictator Mobutu Sese Seko swindled billions and the country was besieged by conflict. They have not qualified for another World Cup.

Haiti, a nation more renowned for voodoo than football, was also experiencing a golden era. Les Grenadiers failed at the last hurdle to qualify for the 1970 World Cup, but booked their ticket to Germany after winning the CONCACAF tournament they hosted. They became the first Caribbean nation to qualify for the World Cup. At the time, 22-year-old dictator ‘Baby Doc’ Duvalier ruled the nation. He had taken over from his recently deceased father, and patron of football, ‘Papa Doc’. The country then fell into ruin after decades of kleptocratic rule and natural disasters. They too have sadly not qualified for another World Cup.

Then there’s Australia: a wealthy nation where many of its citizens ignored football as something played by “sheilas, wogs and poofters” and whose media thought so little of the world game, they didn’t bother to broadcast a World Cup match on television until 1974. Johnny Warren and his Australian teammates saw Neil Armstrong take man’s first steps on the moon in 1969 but had never seen a World Cup match on television by the time they arrived in Germany.

Mysterious kangaroos

The Germans were in a similar situation in never having seen the Australian team play. When the Socceroos arrived, all they saw was a bunch of hapless semi-professional players about to take on the power of the Nationalmannschaft, the relentless East Germany and the wizardry of the Chileans.

Remember, Bild-Zeitung did ask the right question: “How have we ended up with this bunch of no-hopers at the world’s greatest tournament?”

The answer, unbeknown to them, was the incredible esprit de corps that got this bunch to Germany against the odds. A spirit forged by character-building Asian and world tours and by two defining World Cup qualifying campaigns.

This motley bunch was the wonderful combination of Australian-born locals (Johnny Warren, Ray Baartz, Colin Curran), European child migrants (Manfred Schaefer, Attila Abonyi, Ray Richards) and European football absconders (captain Peter Wilson, Adrian Alston, Branko Buljevic, Jimmy Mackay).

In 1969, Australia had played nine matches in their quest to qualify for Mexico 1970.

Four matches in South Korea to knock out the host nation and Japan in a triangular series, three matches (with the eventual help of a witch doctor) to vanquish a stubborn Rhodesia in Mozambique, and then failing at the final hurdle in a heart-breaking 2-1 aggregate loss to Israel. A result that wasn’t helped by a hellish 36-hour trip to get to Israel from Mozambique for a match that was played the following day and an amateur hour lead-up to the crucial second leg in Sydney when the Australian Soccer Federation (ASF) couldn’t even afford to put the players in camp and sent them home.

“Then to really rub salt into our wounds, each player received a cheque from the ASF for the grand total of $13.27 for nine games.” – Johnny Warren

Chasing the dream

The ASF went in search of a new coach to replace Hungarian emigre Joe Vlasits as the new Australian coach. They appointed a 34-year-old World War II orphan from Yugoslavia, who like many others arrived during Australia’s post-war migration boom seeking adventure and opportunity, especially in the game he loved: football.

His name was Rale Rasic.

“I was to receive the princely sum of $2000 per year – that sort of money would be lucky to pay for David Beckham’s bootlace supply for a month – for two years and $3000 for the final two years –$10,000 all up.” – Rale Rasic

Football was a major beneficiary from the arrival of all these ‘ethnics’. A sport that had been played in Australia since the late 19th century, but had stagnated compared to the other football codes, was revitalised by the establishment of new clubs by immigrant communities and football knowledge imparted by men with funny accents.

The corollary was an increase in playing standards and the opportunity to make the dream of playing in the world’s greatest sporting tournament a reality.

The dream came true in November 1973 after another searching qualifying campaign that would’ve broken the character of lesser sides. After narrowly pipping a very strong Iraqi team to top a group also consisting of Indonesia and New Zealand, the Socceroos faced Iran over two legs.

A comfortable 3-0 win in Sydney in the first leg was followed by a tsunami in Tehran as Team Melli, roared on by 100,000 Persians, put the visitors to the sword. The Socceroos were 2-0 down after half an hour. However, through sheer grit and determination they were not breached again. Iran had to wait until 1997 to exact sweet revenge.

One last obstacle stood in the Socceroos’ way, South Korea.

The first leg in Sydney resulted in a disappointing 0-0 draw. Bizarrely, before the second leg in Seoul, in what can be only described as an experiment in reverse psychology gone wrong, the South Korean manager implored the crowd not to cheer any goals scored by the home team.

After half an hour, South Korea led 2-0. The Socceroos’ hopes were fading.

However, almost immediately, in that silent vacuum, Branko Buljevic popped up with a header to reduce the margin. Ray Baartz scored the leveller early in the second half after a goalmouth scramble.

The tie finished 2-2. However, it wasn’t enough to send the Socceroos to Germany as the away goals rule, which doomed the Socceroos in 1997, didn’t exist.

A deciding match was held three days later in a neutral venue, Hong Kong.

On November 13, 1973, a Jimmy Mackay piledriver from outside the box turned the Socceroos’ World Cup dream into a reality.

World Cup reality

So, how did this “bunch of no-hopers” fare in West Germany?

The Socceroos exited the 1974 World Cup after the first round. They lost to East Germany 2-0 after holding their own for most of the game. The East Germans went on to defeat eventual champions West Germany. Although outclassed, they only lost 3-0 to West Germany in a match that won them many local admirers, as many had gone to the match expecting to witness a massacre. They then gained Australia’s first ever point in World Cup history in their final match, a 0-0 draw against Chile. After being outplayed in the first half, torrential rain saw the second half restart delayed by 20 minutes. The change in conditions saw the Socceroos finish strongly and with a bit of luck they could have won the game.

Zaire and Haiti were the only teams to lose all three games. They both conceded 14 goals. Although Haiti did score two and remarkably put one past legendary Italian goalkeeper Dino Zoff, who had not conceded a goal in his previous 12 internationals.

After a 32-year drought, Australia has since 2006 qualified for three consecutive World Cups. We can only hope the Democratic Republic of Congo and Haiti do so again soon and bring some much-needed cheer to their people as only football can.

The last words belong to Bild-Zeitung:

“When Australia was drawn on January 5 to play in the same group as our national team, everyone laughed. What could these greenhorns be dreaming of playing East and West Germany? They will get thrashed… We would like to apologise for the statements we made. We were wrong… The Australians have a wonderful squad. Thank you very much and goodbye and good luck, Aussies.”

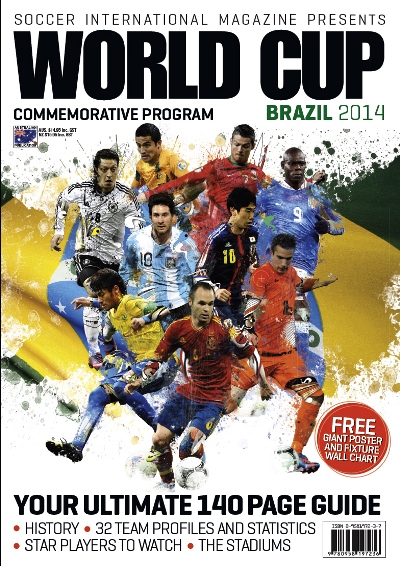

This feature first appeared in the Soccer International World Cup Souvenir Magazine, which previews all 32 World Cup teams and includes features by Athas Zafiris, Jack Lang and Engel Schmidl. It is available from newsagents in Australia and can be ordered from the Blitz Publications online store.