History, as we’re often told, is written by the winners. And if you were to count the number of words expended on the 20th anniversary release of Nirvana’s In Utero album you’d have little choice but to declare Nirvana winners.

They came out on top of the grunge shit-heap. Yeah, Pearl Jam are still releasing new albums; Soundgarden are out there touring; and even the venerable Mudhoney are still doing the rounds. Long live Seattle! But Nirvana still get the most attention, especially from critics, most of whom have been fairly misty-eyed over the remastered release of In Utero.

Ironic (how ’90s), considering Nirvana, and especially Kurt Cobain, were the poster boys of possibly the most self-loathing and loser-obsessed movement in music history – grunge.

We all write our own histories, though. In our heads we keep a scattered and perpetually decomposing version of events that once were; like shedding oxide on cassette tapes kept in a dank room for too long.

Which brings me to another 20th anniversary album release, Smashed on a Knee by the Powder Monkeys, an Australian band that barely scraped the cerebral cortex of mainstream musical consciousness.

It could have been different, however.

The Siren Call of American Success

The Powder Monkeys were a powerful band from Melbourne that extended the Aussie rock heritage of Lobby Loyde, AC-DC and Rose Tattoo into snotty punk attitude, with a dash of free jazz spirit thrown in for good measure. They had guts, spirit and intelligence – a rare trifecta for a rock band.

In the mid-90s the band was courted by American A&R types, including an emissary of big shot producer Rick Rubin, a giant of modern music who has produced albums such as the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Blood Sugar Sex Magik, Johnny Cash’s American Recordings and Jay Z’s 99 Problems – he’s in high rotation right now as the co-producer of Eminem’s latest album, The Marshall Mathers LP 2.

It could be said he knows talent when he hears it. A man of diverse tastes, the spread of acts across Rubin’s labels in the ’90s reads like an Ottoman pasha’s menagerie of the odd and profane: beasts (Slayer), mystics (Donovan), and curiosities (Wesley Willis) abound. There’s no reason to think the Powder Monkeys couldn’t have slotted into Rubin’s zoo alongside the likes of blues rock revisionists Masters of Reality and lo-fi garage rockers Thomas Jefferson Slave Apartments.

At the time, it was even reported in the local press that the Powder Monkeys had signed a three album deal with Rubin’s American Recordings. Explanations for why the deal dissolved focused on the usual music business recriminations about financial agreements allegedly never met by the label. Hardly unusual.

As Powder Monkeys singer-bassist Tim Hemensley explained in an interview at the time, the deal was seen as a way of taking the band to more people rather than trying to become more ‘commercial’.

“While there’s certain types of underground music which have gone pretty mainstream, I still think the music we play is pretty much an underground concern because it’s just too raw for the kids to swallow.

“I wouldn’t imagine that we’re a band that has a huge amount of commercial viability. Thank Christ! And I think that all getting overseas will allow us to do is play to more people, like the people who come and see us here. Just more people I guess.”

The Next Big Thing

The search for the ‘next big thing’ in the wake of Nirvana’s breakout commercial success was still a going concern for record companies in the mid-90s. Money was thrown at all sorts of bands, all in the hope the alternative rock slot machine would pay out again. After all, someone at Capitol Records must have thought signing the Butthole Surfers might pay off one day.

The stigma of “selling out” to a major label had gradually lessened in the wake of Nirvana’s move from mosh pit to Peach Pit, with more and more ‘underground’ or ‘alternative’ bands now willing to make the jump to a major label in search of bigger audiences and maybe even financial security.

It could even be argued the psychological pressure of “selling out” played its part in Cobain’s demise. The sense that his music had now become a soundtrack for the people he loathed, its outsider status turned inside out to become just another fashion item in the pop parade, pervaded much of the commentary attributed to Cobain at the time.

“Jocks have completely taken over music… And just to get back at them, I’m going to start playing basketball.” So the quote goes.

Of course, In Utero was very much Cobain kicking against the pricks (jocks), trying to reclaim his sense of self as outsider. It was why the band picked Steve Albini to record the album, hoping his sharp, dry sound would aid in accentuating the cynicism and alienation of the lyrics penned by Cobain.

Albini’s track record as an underground rock enfant terrible is unimpeachable: as a guitarist-singer he had created the dark, pulsating nightmare that was Big Black, its abrasive follow-up Rapeman, and his longtime excursion into heavy-petting math rock, Shellac. As someone who “recorded” bands — never a producer — he had worked on The Pixies’ debut, Surfer Rosa, an album that apparently had a big influence on Cobain’s songwriting style.

We all know how Cobain’s story ends: drug addiction, depression and a shotgun. Almost as if scripted, Cobain joined the “27 Club”. Another face on a t-shirt sold in bong shops. In Utero became the blood-stained exclamation mark at the end of Nirvana’s short, sharp musical legacy.

Bruised, Battered and Bloodshot

The Powder Monkeys’ debut album, Smashed on a Knee – like In Utero – is also celebrating its 20th anniversary this year. It’s obviously not as well-known as the Nirvana album and isn’t classed by critics as being part of the canon of rock music. But it too has its story.

For a small group of Australian rock fans in the early 1990s – when pubs still stank of ciggies and you could get a pot of VB for $2 – the Powder Monkeys led the charge against the rave menace.

Pubs like the Prince of Wales, the Great Britain Hotel and, of course, The Tote were all rock ‘n’ roll bunkers in the war against the (techno) jive. Forgotten bands like Red Shift; slightly-less-forgotten bands like The Freeloaders; and those that carved out a more sustained legacy, like Hoss, would share the bill at these venues, all dipping into a muddied musical gene pool of 60s garage, 70s cock rock and 80s hardcore.

There were a lot of great bands, as well as some dross that gave you time to duck out to grab a souvlaki or down a few pots in the front bar.

And then there were the Powder Monkeys.

As Radio Birdman’s Deniz Tek says in the liner notes for the Smashed on a Knee reissue: “The Powder Monkeys were probably the hardest rocking outfit in the 90s… They were brutally uncompromising.”

Tek should know. He shared a stage with the Powder Monkeys on a few occasions.

One such occasion was at the old Palace in St Kilda, with the Powder Monkeys opening for Birdman and MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer’s band. This was in 1996, three years after Smashed on a Knee and after the band had released their second album, Time Wounds All Heels. It was around the time when talk of the band signing to one of Rubin’s labels had hit fever pitch.

As the opening band, they put in a blistering set that left Birdman and Wayne Kramer with little to play for. It was a performance in keeping with the Jerry Lee Lewis ‘I’m going to set my piano on fire, now top that’ school of opening act etiquette.

The Powder Monkeys were on a roll that night and they weren’t going to stop; even as the house lights came up, the curtain began to close, and the house PA was cut, they would not go gently into that good night.

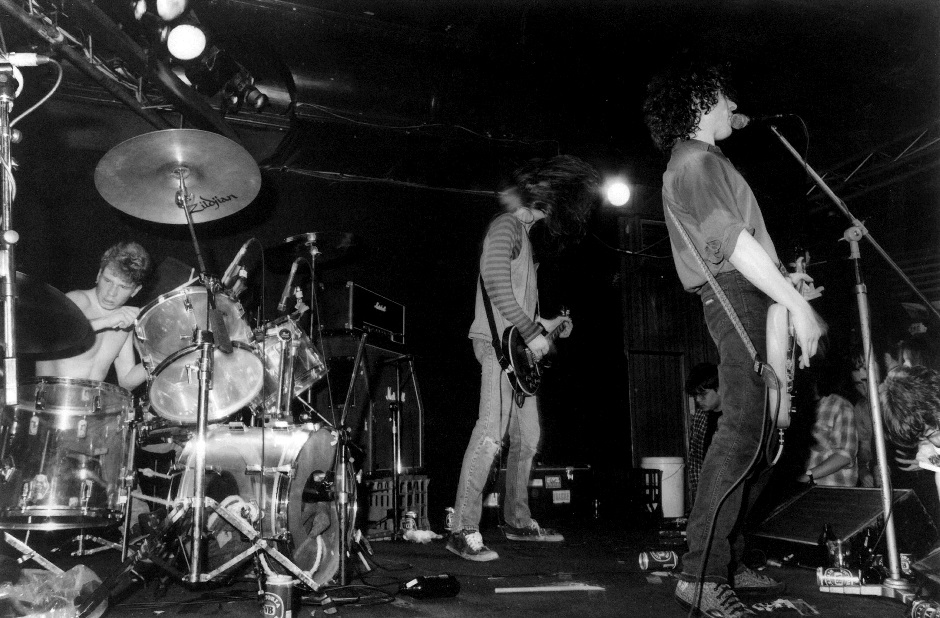

(There’s not a lot of decent Powder Monkeys footage on YouTube, but this gig from 1992 at the Hopetoun in Sydney isn’t too bad.)

For those who had been going to see the band since their formation in 1991, this sort of performance was par for the course – even more so once they had slimmed down from a five-piece to a power trio. Keen students of rock ‘n’ roll, they had distilled the best bits of the bands they loved – Motorhead, Thin Lizzy, Black Flag – without being too slavish about it.

A few years earlier I had seen Nirvana at the same venue just as they were hitting the heights of “Teen Spirit” mania. It was one show, so hardly the basis for a blanket judgment, but as far as live sets go there was little comparison – the Powder Monkeys were far and away the better live band.

Again from the liner notes of the reissue, Deniz Tek captures something of what the Powder Monkeys were about: “In the aftermath of depressing flannel-shirt junkie Seattle drone, I was so happy to find out that the essence of rock ‘n’ roll was still alive.”

The Beginning of the End

The Powder Monkeys released a couple more really good albums after Smashed on a Knee. But they never really got that opportunity to extend their audience in the way promised by that much-speculated Rick Rubin deal. In fact, by the early 2000s the band had descended into a morass that had become all too common in the Melbourne music scene at the time, one that had also afflicted Seattle in the wake of the grunge good times.

In an extensive interview with Patrick Donovan for Mess + Noise, guitarist John Nolan explains a big part of the reason for the band’s eventual demise.

“The thing I remember the most about the second LP was that it was when my junk habit was getting out of control. The first LP was totally pre-junk for the band. With the second, I sort of was the first to really get a habit.”

Still a devastatingly great live band when they hit their straps, they had nonetheless lost some of their spark; whether it was the drugs, the disappointment of the Rubin deal going bad, or just having to play the same old eastern seaboard circuit Australian bands have to plough to ply their trade, the band had started to look tired.

In late 2001, John Nolan had suffered a severe asthma attack and was officially declared dead in hospital. He was somehow resuscitated, but the damage to his brain and body meant he spent the next year in rehabilitation learning to walk again. The band was put on hiatus. It had been a terrible year for Melbourne’s rock scene, with Tim Hemensley’s former bandmate, Sean Greenway, dying from a heroin overdose in January. It was one of a few overdose deaths in the scene.

In the meantime, in a pleasant middle Melbourne suburb not far away, the Cester brothers had formed Jet, a band that would go on to achieve the sort of pop chart success the Powder Monkeys would never have entertained. Jet became the pop face of Melbourne’s rock scene, a sort of Pat Boone to the Powder Monkeys’ Little Richard.

In July 2003, Hemensley, the pocket-sized dynamo that kept the Powder Monkeys’ heart beating, died of a heroin overdose. It knocked the stuffing out of Melbourne’s musical soul.

The Powder Monkeys might not have attracted the type of attention or acclaim Nirvana did, but for those who were there, especially in those blazing early days, they remain a great, great band that, dare one say, could have achieved a whole lot more. In that way, they’re not too dissimilar to Nirvana.

Smashed on a Knee is released by Freeform Patterns.

Smashed on a Knee is now also available on vinyl via Desperate Records.

Powder Monkeys will be performing at Cherryfest 013 on November 24.