The World Cup has lost one of its great craftsman with the exit of Italy and Andrea Pirlo from the group stage.

“Don’t play what’s there; play what’s not there.” – Miles Davis

In his seminal coaching treatise Teambuilding: the Road to Success, legendary Dutch coach Rinus Michels talks about the team functioning as an orchestra, with the players as the musicians and the coach as the conductor.

He uses the example of the great 20th century American conductor Leonard Bernstein to illustrate how the coach of a football team, in a similar way to the orchestra conductor, must work with his players to create a cohesive unit that can successfully attempt to grapple with the match and opponents at hand.

“Football coaches have often been compared to conductors. Every musician plays his own role and instrument in an orchestra. It is not only the task of the conductor to ensure that every one of the individual musicians is able to contribute, he must also ensure that the result is harmonic.”

He then compares football to gridiron (American football), noting that gridiron is a “coaching-based sports discipline”, while football is more accurately characterised as a “players’ sports discipline”.

“In American football, but also in other sports, tactical situations for the team can be rehearsed over and over again. Coaches indoctrinate these patterns. Not the unpredictability, but the predictability dominates these sports.”

It is a subtle difference and one that leads to the idea of football being played not by an orchestra led by a conductor interpreting a written score (the archetypal gridiron coach with clipboard in hand reading from his playbook about to be doused in Gatorade), but by an ensemble riffing on a melody, bending it, stretching it and making something new.

The players are given agency to exercise their skills and intelligence in order to create.

“The players themselves are the directors. Only they can solve the situations while improvising,” Michels goes on to say.

This sounds more like jazz than classical music.

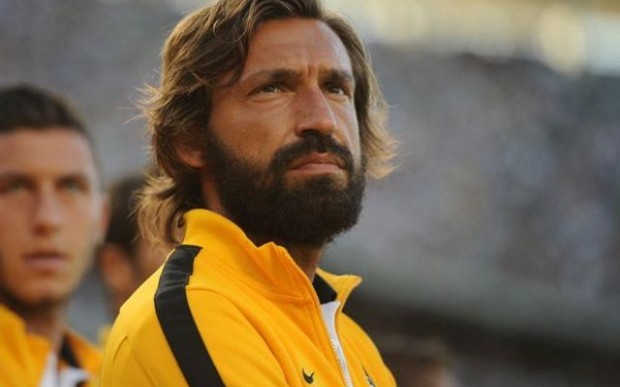

Italian midfielder Andrea Pirlo has long gone by the nickname Mozart, but the comparison to music greats might better be made with Miles Davis, or in keeping with Pirlo’s Sinti-gypsy heritage, he could be compared to the prímás in a gypsy band — the lead musician, usually a violinist, who sets the playing pace and mood for his bandmates with his own playing.

Both the American trumpeter and the Italian playmaker epitomise cool in their respective fields. It helps too that, culturally, Black Americans and Italians are both groups which historically carry a heavy cachet of cool.

With his beard, shoulder-length locks and lean physique, Pirlo looks out of place running around on a field filled with tattooed faux-hawk poseurs and jack-the-lad-a-likes, as if he wandered in accidentally from a conference for architecture academics.

It says something about the man’s sense of self and humour that his recently released autobiography is called I Think, Therefore I Play — a nod to the oft-referenced Rene Descartes axiom Cogito ergo sum (I think, therefore I am).

Pirlo is possibly the pre-eminent thinking man’s footballer of our time. In this regard he might even surpass the Barca pairing of Xavi and Iniesta, who for all their wonderful tiki taka mastery still manage to come off like Peter Pan characters, or Tintin and Astro Boy.

At the age of 35, he is still gracing the world stage, gliding about the field with the same soft-shoe shuffle that has been deceiving opponents since he was just a boy from Brescia (the same club where another great Italian playmaker, Roberto Baggio, got his start).

If the title of his autobiography puts a football twist on Descartes then it is probably fair to allude to another of the French philosopher’s hand-me-downs when talking about the beguiling spell Pirlo casts upon his opponents: démon maléfique.

“I will suppose therefore that not God, who is supremely good and the source of truth, but rather some malicious demon of the utmost power and cunning has employed all his energies in order to deceive me.” (Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy)

Poor England goalkeeper Joe Hart must see horns, hooves and a demonic trident each time he steps onto the field against Pirlo. Just think about that ‘Panenka’ penalty at EURO 2012 and then, in this World Cup, that free-kick, executed with nonchalant cool, which swerved and dipped as if it was remote controlled.

Historically, and sadly, the English national team tends to shunt creative types like Pirlo off to the sidelines, often applying a strange time-and-motion study rationale to the utility of these types of players. Even the bureaucratic Belgians could find a spot for the sublime touch of an Enzo Scifo, whereas Matt Le Tissier’s brand of genius (which inspired Xavi as a youngster) earned him a paltry eight caps for England.

Compare that attitude to the 2006 World Cup-winning squad of Italy, which included not only Pirlo, but also Alessandro Del Piero and Francesco Totti — how’s that for some fantasia football firepower.

But Italian football has not always been receptive to the genius playmaker. In fact, a realist strand of thought has long held that these regista (directors) can be detrimental to the effective functioning of the team. In the harshest of these critiques, these players are referred to as abatini – a term which roughly translates as fops and was first coined by revered Italian football journalist Gianni Brera – players who don’t do a lot of work and stake their claim to a place in the team based on the occasional flash of magic.

Brera used the term to describe another of the great Italian playmakers, Gianni Rivera. He said of Rivera: “If you have Rivera, you have to build the team around him.” This was both lauding Rivera’s powers but also cautioning against the folly of putting the team’s wellbeing at the feet of one player, the errant boy wonder.

Maybe the heartbreak England experienced building a team around their own flawed genius, Paul Gascoigne, put paid to any more thought of indulging in such an experiment again. Why play in 5/4 time when 4/4 will do?

Maybe Brera just wasn’t a jazz fan?

However, it would be wrong to think of Pirlo as a player who just swans about the place, pulling out a trick whenever the mood takes him. Watch him play and you soon realise a lot of what he does is not flashy grand gestures, but tight, economical riffs played with exquisite skill.

While Steven Gerrard will sometimes lapse into an Eddie Van Halen-like quest for the most spectacular Hollywood Ball, Pirlo keeps his audacity on a tighter leash, only busting out the whammy bar effects when the tune really calls for it. Much of the beauty in Pirlo’s work is in the little details; the fleet one-two; the deft touch that will coax a fullback into attack; the back-heel that opens an acre of space for a fellow midfielder; the dummy sold to create a scoring chance.

Michels was of course well aware of the tension that could be produced by the inclusion of a playmaker in a team, the way in which such an element could disrupt the cohesive and balanced functioning of the unit. After all, his greatest protégé was the original Dutch master, Johan Cruyff, a virtuoso footballer whose sheer natural talent always carried him to the very edge of the individual vs team precipice.

“For the real fans of the game the specific football qualities of such players give the game an extra dimension. These players are indispensable, for both teammates and coaches, if they efficiently put the extra quality they possess to use for the team.”

Like Miles Davis, Pirlo has weaved his magic over the years with a myriad of combos: some classic (Kind of Blue, Azzurri 2006), some not so classic (Amandla, Azzurri 2014), but always interesting.

Pirlo and his Azzurri combo have bowed out of this World Cup — his last — but not before football fans were once again treated to the understated charms of the Juventus star. Thankfully, after signing a contract extension with the Turin club, we’ll still have at least another two seasons of his magic to savour in Serie A and the Champions League.