In his autobiography, Bob Dylan told a story about how professional wrestler Gorgeous George once came through his hometown of Hibbing, Minnesota, and happened to see the young Robert Zimmerman playing a show. It was a revelatory moment for the young folk singer.

“He didn’t break stride, but he looked at me, eyes flashing with moonshine. He winked and seemed to mouth the phrase, ‘You’re making it come alive’,” Dylan recalled in his autobiography.

It seems too good to be real; a cinematic retelling of a moment latent with the power of invisible history.

In that moment of recognition, a synapse in Zimmerman’s brain lit up and illuminated a neural pathway to greatness. He had been awakened to the cosmic potential of the dialectic elixir of being both master of his universe and just another piece of microcosmic dust, all and one in the same moment. The con as part of consciousness; the sham in shaman; artist and flim-flam man as one. The wrestler unmasked only to reveal another mask.

The larger-than-life flamboyance of Gorgeous George was also said to have influenced the braggadocio of Muhammad Ali and James Brown, the type of exaggerated boasting and preening that would enthrall fans and irritate detractors. The egotistical puffery flirted with queerness, riding dangerously close to accepted ideas of how male performers were expected to act, subverting the rigorous stoicism of the Greatest Generation’s male mythmaking.

Gorgeous George made many red-blooded jarhead patriots laugh, but he also made them uncomfortable. Where did the theatre end and the reality begin?

Of course, only a few years later Dylan would, in wrestling parlance, do a classic “heel turn” for a section of his fans when he went electric in 1966. The infamous “Judas” heckle that met Dylan when he played an electric set with his backing band, The Hawks, at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall was a sign to his traditional folkie base that Dylan had sold out to the burgeoning rock scene and gone pop. He’d betrayed his roots, himself and his fans.

In going from good guy “face” to bad guy “heel”, his folk fans thought Dylan had gone from being an artist to a pop star; this was still a time when rock music was struggling to establish its credentials as “real” music, an art form in its own right rather than just another musical fad manufactured by the booming postwar youth culture’s appetite for novelty.

In many ways, rock music faced the same question of legitimacy as professional wrestling: both forms were bastard offspring, rock music’s progenitors being the blues and country, and professional wrestling’s being amateur/college wrestling and Greco-Roman. Rock music was not seen as real music and professional wrestling was not seen as real sport – both were tainted by showbiz; low-minded, crass and financially motivated entertainment at that.

For rock music, the standard retort was, “That’s not music; that’s just noise.” For wrestling, “You do know wrestling’s not real?”

It was trash entertainment for mostly young, lower class men.

Climb the turnbuckle high,

Take two falls out of three,

Blackout for local TV.

(Southwestern Territory)

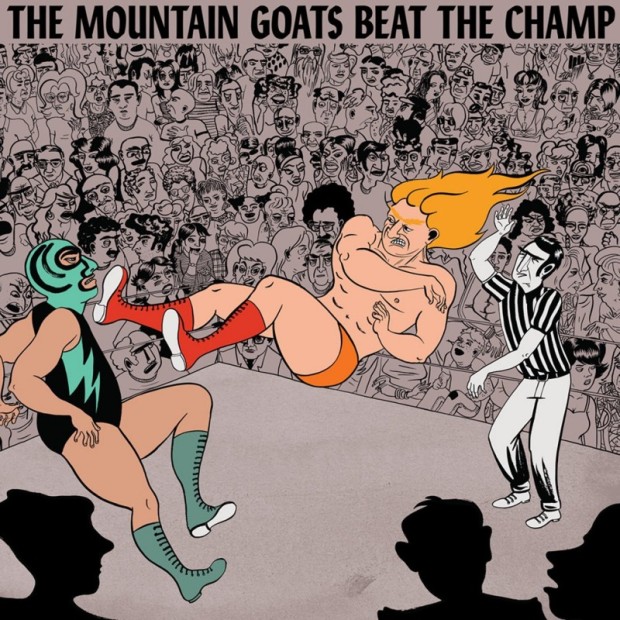

The Mountain Goats’ Beat the Champ might be the greatest wrestling concept album ever made. Sure, the field is not exactly brimming with competition. This does not detract from its brilliance. It’s touching, funny and poetic, taking the listener on a journey through the ins and outs of the professional wrestling world, from the doleful opener Southwestern Territory to the haunting closer Hair Match.

It’s not the Gorgeous George-inspired Dylan that comes to mind listening to John Darnielle’s novelistic lyrics about the wild west characters of wrestling’s golden age. The detail in his lyrics, the intimate knowledge he has of his subject matter, and the pathos and sadness that permeates it all recalls the best work of David Ackles, a somewhat forgotten American singer-songwriter of the 1970s, and especially the album that is considered by critical consensus to be his greatest work, American Gothic.

Darnielle’s reedy voice sounds nothing like the gruff Ackles – Bill Callahan is a closer fit in that department – but the lyrical stains and creases Darnielle brings to life do recall the forensic eye of Ackles. This is accompanied in musical spirit by his longtime Mountain Goats bandmates, bassist Jon Wurster and drummer Peter Hughes, and given tonal depth by the string arrangements of New York downtown scene veteran Erik Friedlander.

The album recalls Darren Aronofsky’s film The Wrestler: lifting the mask to reveal what’s underneath while affirming pro wrestling’s strange power as an athletic vehicle for storytelling through songs like The Legend of Chavo Guerrero.

Before a black and white TV in the middle of the night

I’m lying on the floor, I’m bathed in blue light

The telecast’s in Spanish, I can understand some

And I need justice in my life, here it comes.

With its dense layer of loving references to wrestling’s heroes of yore (Chavo Guerrero, Bruiser Brody, Iron Sheik to name a few) Beat the Champ is an album plenty of wrestling fans will enjoy. But it also works as a tour de force of songwriting that non-wrestling fans can dig as well. It’s truly the undisputed heavyweight champion of indie rock wrestling albums.

Rock music and wrestling both had their “golden age” in the postwar economic ‘long boom’ from the early 1950s through to the mid-1970s. Both forms gave their young fans and participants an arena in which to lose themselves and become immersed in the fantasy world on offer; whether that was the endless teen summer of rock’n’roll or the good guy vs bad guy storylines and staged physicality of wrestling.

The Mountain Goats’ Beat the Champ presents a different mode of dealing with wrestling as subject matter for rock music from The Dictators, who were possibly the greatest exponents of wrestling-influenced rock.

While Beat the Champ tells stories from an authorial perspective about wrestlers and wrestling fandom, bands like The Dictators assumed the postures and vernacular of pro wrestling to infuse their songs and the band’s persona with a sort of jokey adolescent goof-off quality that worked well with their whole “cars, girls, surfing, beer, nothing else matters here” take on teenage life in the 70s.

The ‘young, fast and scientific’ Dictators were, of course, blessed to have their ‘secret weapon’, Handsome Dick Manitoba, a roadie-turned-singer who was able to pull off the bigger-than-life buffoonery required to make the wrestling angle work for the band.

I just come back from Minn-e-a-polis.

Where I just beat Verne Gagne and Dick the Bruiser, daddy.

There ain’t no–you can bring on Haystack Calhoun, Eric Bloom,

I don’t care who you bring here, daddy. Rainbow, Strongbow.

They’re all going under the THUNDER OF MANITOBA.

(Two-Tub Man – The Dictators )

Like Robert Johnson meeting Satan at the crossroads, there are plenty of examples of the immovable object of wrestling meeting the irresistible force of rock’n’roll, an unholy tag-team alliance of beats and beatings.

Just like The Dictators, another New York band, the Beastie Boys, also took a lot of their cues from the over-the-top delivery and behaviour of professional wrestlers. Beastie Boys producer Rick Rubin is a massive wrestling fan and even put money into a promotion himself at one stage. He saw that the Beastie Boys needed an angle, a gimmick to work, if they were going to distinguish themselves as white-rappers-with-a-punk-background in the Golden Age of Hip Hop back in the 1980s.

“There’s no question that, early on, the Beastie Boys were very influenced by pro wrestling.One-hundred percent. The idea of being bad-guy rappers, saying really outlandish things in interviews, that all came from a love of pro wrestling,” he told Rolling Stone magazine.

In his classic book on the Memphis music scene, It Came From Memphis, author Robert Gordon devotes a whole chapter to the impact that wrestler Sputnik Monroe had on race and segregation in Memphis during the late 50s and 60s.

The chapter, entitled ‘The World’s Most Perfectly Formed Midget Wrestler’, details the relationship between Sputnik and famed Sun Records producer Sam Phillips, particularly Sputnik’s mentoring of Phillips’s son, Jerry.

In what is truly a story that could only have happened on the wrestling circuit of the American South in that era, Sputnik came up with a promotion featuring midget wrestlers, which included the short but athletic 12-year-old Jerry Phillips, who was soon dubbed ‘the world’s most perfectly formed midget’. Wrestling crowds knew it was a crock, that Phillips wasn’t a midget, but that was part of the whole idea, to rouse the anger of the crowd: “That one don’t belong! He ain’t no midget!” audience members would scream.

But a big part of the Sputnik Monroe story was that he was a white wrestler who had a massive following among black fans, and he actively sought their support. Sputnik is credited with being one of the biggest agents for positive change when it came to integration at wrestling events in the 1950s, which was a precursor to integration at other social events. Monroe’s belligerent stance on race made him a reviled figure among white parents and conservatives.

In Gordon’s book, Memphis sportscaster Johnny Dark recalls an episode in Louisville, Kentucky, that illustrated the esteem Sputnik was held in by his black fans:

“In the dressing room, this little black lady came up to Sputnik, she had tears in her eyes, she said, ‘You don’t remember me, you never met me, but I used to live in Memphis when they made us sit upstairs in those buzzard seats.’ She said, ‘You’re the one who got them to change that.’ That was the first time I saw Sputnik with tears in his eyes.”

(Have a look at Norwegian band Gluecifer’s tribute to Sputnik Monroe.)

Trash rockers The Cramps did a terrific cover of wrestling rock classic The Crusher, which was originally recorded in 1964 by Minneapolis garage band The Novas. The Novas wrote the song as a tribute to tough guy wrestler Crusher Lisowski, complete with the classic lyric, “Do the hammerlock, you turkey neck!”

Australia had its very own masters of psychedelic wrestling rock, the Psychotic Turnbuckles, who did a great version of The Crusher too. The Turnbuckles came out of the Sydney ‘Detroit’ rock scene and played hard and tough versions of 60s garage classics as well as some originals. The band’s insane live shows usually involved some form of grappling interaction with audience members brave enough to take on the might of vocalist ‘Jesse the Intruder’. It was truly wild times with the Pharaohs of Far Out whenever the band played live.

The band even had a back story explaining its turn from wrestling to rock’n’roll, which involved the “former professional wrestlers” moving to Australia from their hometown of Pismo Beach, California, after being banned from the Pismo Beach Wrestling Alliance. (Adelaide scuzz rockers the Iron Sheiks also put on a pretty decent wrestling-inspired show, taking their name from everyone’s favourite Persian grappler and Twitter identity.)

Another curio of the wrestling-rock crossover genre is the totally weird collaboration between Portland wrestler and a 17-year-old Greg Sage, who would later go on to be the driving force behind one of the seminal US punk bands of the late 70s and 80s, The Wipers. Beauregarde – who also sometimes went by the names of Eric the Golden Boy and Beautiful Beauregarde – recorded the eponymously titled album in 1971, with Sage on guitar, and it has become a bit of a hit among soul-funk crate diggers. It certainly doesn’t sound anything like the hard-rocking desolation of The Wipers, but it is very cool.

Bob Mould of Husker Du and Sugar had an even more intimate involvement with the world of professional wrestling when he took a sabbatical from his life as a musician in the late 1990s to work as a scriptwriter and showrunner for the World Championship Wrestling (WCW) promotion. Mould was a keen wrestling fan and knew the sport inside out. He understood the textures and complexity of how wrestling worked as a narrative form.

“That was a hard job. It was like writing a Broadway show every night, and there’s no off-season,” Mould told SPIN magazine.

Then of course there was the great wrestle-rock collision of WrestleMania, the megacard WWF event in 1985 that really signalled the coming corporatisation of the sport. It was also about the same time that rock music was starting to get slicker and more ‘corporate’ with MTV and compact discs. Among the participants at WrestleMania was pop star Cyndi Lauper, who was in the corner of women’s champion Wendi Richter. Part of Lauper’s wrestling shtick also involved having lunatic wrestling manager Captain Lou Albano play her father in the video clip for Girls Just Want to Have Fun.

There was always something very wrestling about the whole make-up persona shtick that made KISS so famous. KISS gave glam rock a horror movie twist that could’ve gone over as easily in the wrestling arenas as it did the rock arenas of the 1970s. The band cemented the conceptual ties with wrestling when a Gene Simmons-like character “The Demon” was licensed to the WCW as a regular in-ring performer in 1999. The character lasted about two years and soon after his debut The Demon (which possessed the body of wrestler Dale Torborg) was soon on the wrong end of squash matches.

An example of another wrestler crossing over to the music world (ala Beauregarde but not as good) is the self-proclaimed “Ayatollah of Rock n Rolla”, Chris Jericho. Among the biggest stars of wrestling in the past 10 years, Jericho has also forged a career as a rock singer with the band Fozzy. He describes the band as “If Metallica and Journey had a bastard child, it would be Fozzy.”

Not sure Metallica and Journey should ever have got that drunk and spawned such a beast, but Fozzy have their fans. It’s certainly a long way from the indie rock sounds of the Mountain Goats.

That’s just scratching the surface of the battle royal cage match of wrestling and rock music collisions, we haven’t even delved into the truly bizarre world of wrestle-rock albums that featured the outsized talents of wrestlers like Classy Freddie Blassie, “Boogie Woogie Man” Jimmy Valiant and various rappin’ wrasslers. Throw in all those rock’n’roll gimmick wrestlers like Honky Tonk Man through the ages, plus contemporary stars like CM Punk, and you’ve got a pretty extensive and bizarre array of wrestle-rock crossover action.