Blacks and “Blacked-Up Whites” v Whites: The story of the strangest game of footy ever played

On Monday, June 11, 1900, Melbourne’s The Argus newspaper reported that a charity match was “played between 20 representatives of the Healesville Aboriginal Station and a team selected from the Moreland Club at the Coburg Recreation reserve on Saturday afternoon.” Athas Zafiris investigated further and uncovered how six white players had to “black up” to play for and Aboriginal team because of the colonist inhumanity to to our First Australians. Here is the story of the strangest games of footy ever played.

On Saturday, June 9, 1900, in the Colony of Victoria, six months before the Federation of Australia, in the shadow of Pentridge Prison, in the northern suburb of Coburg, the young city of Melbourne, the very place that gave birth to what became known as Australian Rules, hosted a football match, the strangest match in Melbourne’s history.

It also inspired one of the most remarkable accounts of a game of football ever published in the history of this country.

It was published in The Coburg Leader on Saturday, June 16, 1900.

Once you acknowledge the standard English colonial racism of the time, the author displays a dry wit and, more importantly, an arresting candour about white “civilised” conquest and Aboriginal dispossession.

Here is the text in full as it appeared in the paper on that day.

ABORIGINAL FOOTBALL

BLACKS V. WHITES

A band of aborigines, on Saturday last, came from the Korranderk station at Healesville to re-visit the scene of their old-time korroborees, on the Coburg Recreation Reserve. But it was not to go through any heathenish or ghostly ceremony, as in the dark age before the advent of Cr. J. W. Fleming and other white pioneers that the dusky warriors returned to the once familiar spot. True they were under the nominal leadership of a hoary potentate, ” King Billy ” o’ that ilk, and the oldest native savage at present in the colony; but sovereign above him was a white fellow, namely, Mr. E. F. Barry, and though armed with boomerangs and carrying fire-sticks they came not to fight, but what is frequently a not less gentle pastime, to play at football, against a team of Moreland, North Brunswick and Coburg ” white ” players, and for the sake of helping the funds of the “white fellows'” hospital, not to fill it. The Coburg people recognised the magnanimity of the visit and turned out in thousands, to patronise the performance.

There must have been something strange in the feelings of King Billy and his braves as they filed out into the playing area of the reserve, each man attired in football ” toggery,” of mixed make and color, when they gazed upon the trim turf of alien grasses, so assiduously watered at the shire council’s expense, beneath their feet, and the strange English trees that have taken the place of the beloved and more beautiful gum that was want of flourish there in the time when the Jika Jika tribe warred with the Yarra Yarra’s across the verdant stretch now covered by the gloomy stockade buildings. And if King Billy were a philosopher he would probably have meditated with some emotion of bitter satisfaction that the present possessors of his country and the exterminators of his race had brought hither what civilized people always bring first to a new country, a cemetery and a prison.

The football match was as interesting as was anticipated. “King Billy” captained the visitors and Mr. H. Toll the “whites” team. The blacks showed a wonderful mastery of the best points of the game, being amazingly agile in running and dodging. King Billy travelled like lightning and appeared to be in every part of the field at once. The whites won with a narrow margin, the scores being Whites 6 goals 6 behinds, Blacks, 5 goals 5 behinds. After the game, out of which the blacks came as fresh as paint, there was a splendid exhibition of boomerang throwing and lighting fires by means of stick and tinder. The gross takings for the day were £23 7s, including £2 as donations. The spectators, amongst whom were Mr. David Methven, M.L.A., and several of the shire councillors, left the ground highly delighted with the day’s entertainment. It is probable that about £18 will be paid into the hospital fund as a result of the effort. The blacks were, after the match, entertained at the LaBelle tea rooms, Sydney-road, Brunswick. It is probable that the team with addition of several full-coloured aborigines, will again visit the district at an early date; it is safe to predict for them a hearty reception.

What did the writer mean by the “addition of several full-coloured aborigines”? Who was this “King Billy” “who travelled like lightning”? Who was Mr. E.F. Barry (the man in charge)?

Our correspondent painted a canvas with dazzling, broad strokes. But out of ignorance or convenience he left out the details, especially one very important detail: All was not what it seemed on the Coburg Recreation Reserve that day.

But, before we unravel these mysteries, here’s a quick history lesson to provide some context.

In 1835, the year of Melbourne’s founding, the Aboriginal population south of the Murray River, was estimated to be 15,000. However, the preinvasion population was estimated to be as high as 60,000. Epidemics, like smallpox, brought in by European settlers decimated the Victorian Aboriginal population before many had even laid eyes on a white man.

By the time we get to 1900, the year this match was played, the Aboriginal population in Victoria had dropped to approximately 850. In the meantime, 1.2 million white settlers with their 11 million sheep and 1.6 million cattle also called Victoria home. It was a human catastrophe. In the space of a century, an ancient indigenous culture, tens of thousands of years old, had almost been wiped out.

In order to “protect” the Aboriginal population, the Victorian Government set up seven Aboriginal reservations. Coranderrk, established in 1863, 50km north-east of Melbourne, was one of them. But this protection came with caveats as it marked the beginning of the coercive administration of indigenous people that we still see in some parts of Australia today.

Unfortunately for the inhabitants of the self-sustaining Coranderrk station, their fertile land was desired by the neighbouring white farmers.

In 1886, the government introduced the “half-caste act” as a way to forcibly integrate half-caste Aboriginals into the general population. Every “half-caste” Aboriginal under the age of 35 had to leave the reserves.

The legislation caused enormous distress for Aboriginal communities. Wurundjeri tribal elder and activist William Barak unsuccessfully petitioned the Victorian Government on behalf of the people of Coranderrk.

Could we get our freedom to go away Shearing and Harvesting and to come home when we wish and also to go for the good of our Health when we need it…We should be free like the White Population there is only few Blacks now rem[a]ining in Victoria, we are all dying away now and we Blacks of Aboriginal Blood, wish to have now freedom for all our life time…Why does the Board seek in these latter days more stronger authority over us Aborigines than it has yet been?

Coranderrk’s days were numbered. Many of the removed Aborigines, unable to find work in the general community, ended up living in worse circumstances as they set up shanty towns next to reserves to be close to their families.

By 1900, only 82 Aboriginal residents belonged to the station.

Incredibly, the “black” men of Coranderrk and their exiled “half-caste” brothers were able to field a football team. In 1896, they played against the neighbouring townships of Healesville, Lilydale and Yarra Glen in the “Allan-Russell Trophies Competition”. In the years that followed, Coranderrk would play the odd friendly game against their local rivals, but for logistical and “administrative” reasons it became too difficult to get a team up for a home and away season. As a result, their best players ended up being invited to play for the neighbouring teams, especially Healesville.

One of the white players who played for Healesville was a fellow named Mr. E.F. Barry. He would’ve been well acquainted with the Aboriginal footballers of Coranderrk, both as opponents and as team mates, and if he didn’t come up with the idea of taking an Aboriginal team to the big smoke to showcase their football skills to an inquisitive public, then he certainly appeared to be the man in charge.

Unfortunately for Mr. Barry and his Aboriginal mates the best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry.

In this case, sadly, strangely wrong.

On Friday June 15, 1900, six days after the match, the Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian filled in the missing pieces to the jigsaw puzzle of the match played in Coburg to its small local readership.

Here is an abrigded version of the article.

FOOTBALL

BLACK V. WHITE

Some little time since, a movement was set on foot in Coburg and Moreland Road, whereby it was sought that a team of Coranderrk aboriginals should be invited down to the first named suburb, there to play a football match in aid of the funds of the Melbourne Hospital. Arrangements were accordingly made down there for the proposed charity match. Handbills were printed and distributed, announcing the object and form of the match. The patronage of the Coburg Council was obtained, tickets were printed and distributed for sale, and everything portended a gigantic success. So far so good. The manager of the affair, Mr. E. Barry, then waited on Mr. Shaw, manager of the Coranderrk station, on Tuesday of last week, and asked that gentleman’s permission to allow as many blacks as convenient to go. As he (Mr. Shaw) had not previously been consulted in the matter, the request came somewhat as a surprise, and that gentleman felt himself placed somewhat awkward. Mr. Shaw expressed himself that he could not do anything in the matter until he received word from the Board, and accordingly a communication was sent to the secretary on Wednesday evening explaining the circumstances. It was too late, however, in the day to arrive at a satisfactory settlement, so the services of some colored individuals in Melbourne were engaged, and as it was thought that a few could be had from here outside of the station, it was decided to make the best of it by having the remaining players blackened up. The men journeyed down by the morning trains on Saturday, but E. McDougall and W. Abbott were the only colored men from Healesville. The visitors lined up with 17 men, and though from a distance some of them looked fairly well, at close quarters they needed but little inspection to determine the familiar features of the half a dozen who “had the black on.” The match was witnessed by some 2000 people. Though it is a matter for congratulation that the movement resulted successfully, it is none the less regrettable that the people who attended were “gulled” into the belief that they were going to witness something exceptionally good. The whole fault arose through the promoters of the affair making arrangements before they knew whether the blacks would be allowed to go.

In reality, what we got was Blacks and Blacked-Up Whites versus Whites.

It is revealing that the local newspaper displayed more concern for the paying patrons who were fooled into paying for something that was not as opposed to the appalling, dictatorial bureaucratic Catch-22 that thwarted Mr. Barry from bringing his “protected” Aboriginal football troupe down to Melbourne.

The show had to go on for Mr. Barry and one can’t begrudge him for his efforts. Tickets were sold, all for a good cause, so they had to make a fist of it. The event turned out to be a success, due in part to the white men who “had the black on”. I would venture to guess they were Mr. Barry’s Healesville team mates who had come to his rescue in his hour of need.

As a result this motley collection of individuals helped play a part in what must rank as the strangest game of football ever played in Melbourne.

One week after this strange game, on Saturday June 16, 1900, the Coranderrk team hosted Healesville in a scratch match.

The final score read Coranderrk 4 goals 8 behinds; Healesville 4 goals 6 behinds. E McDougall, Gibbs, Harrison, Robinson, Wandin, and Macrae shone out prominently on behalf of the winners.

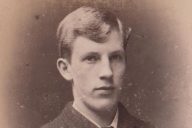

Edward McDougall or “King Billy” according to our correspondent from The Coburg Leader was not “the oldest native savage at present in the colony.” Far from it. The captain of Coranderrk who “travelled like lightning and appeared to be in every part of the field at once” was only 30 years of age when he succumbed to tuberculosis and passed away in February, 1904.

This is how the Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian reported his death.

It will come as a surprise, tinged with regret, to local footballers to learn of the death of “Teddy” M’Dougall, late of the Coranderrk Station, which occurred at Lake Tyers recently. As an exponent of our winter pastime, deceased had few equals, and the services he has rendered Lilydale and Healesville football will not be forgotten for years. He was a very manly player, as his opponents and associates always testifed to, and his death removes another of the fast declining aboriginal race.

In 1911, the Coranderrk team was resurrected for one season and won the Stevens Trophy, finishing above Healesville, Lilydale, Yarra Glen and Coldstream.

In 1952, James Wandin, ngurungaeta (tribal leader) of the Wurundjeri and great-great nephew of William Barak, became the first player of Aboriginal descent to play for St Kilda Football Club.

He was the last person born at Coranderrk Station.

Postscript

As I was researching this piece, I came across an astonishing letter that was published in the Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian on September 22, 1899. It begins with a complaint about the behaviour of the Healesville Vice-President, but after a bitter recent defeat by the football club due to the absence of their Aboriginal players, the letter concludes with a scathing attack on Mr. Shaw, the manager of Coranderrk station, and the despotic treatment of his Aboriginal subordinates.

Very little danger was feared at losing, provided the best team could be got together and, accordingly, Mr. Shaw, superintendent of the Coranderrk station, was interviewed, with the object of asking him to allow certain men on the station to play, hut here a greater stumbling block barred the way. With the utmost respect for Mr. Shaw, he could not be swayed by any means into allowing the chosen few to play in this very important match. Entreaty was of no avail, and the yoke of despotism was enforced by that gentleman, with the result that the Healesville team lost the match through the Coranderrk players not being allowed to take part. The refusal of Mr. Shaw to grant this liberty to his subordinates opens up a field for argumentative opinion, but it is not my desire to cause strife in such a direction. In fact, to speak it plainly, two unredeeming traits heir to human nature, stand out prominent in the actions of both gentlemen, savoring strongly of “Man’s Inconsistency!” and “Man’s Inhumanity to Man.” Yours, &c., FAIR PLAY.

“Man’s Inhumanity to Man.”

Indeed.

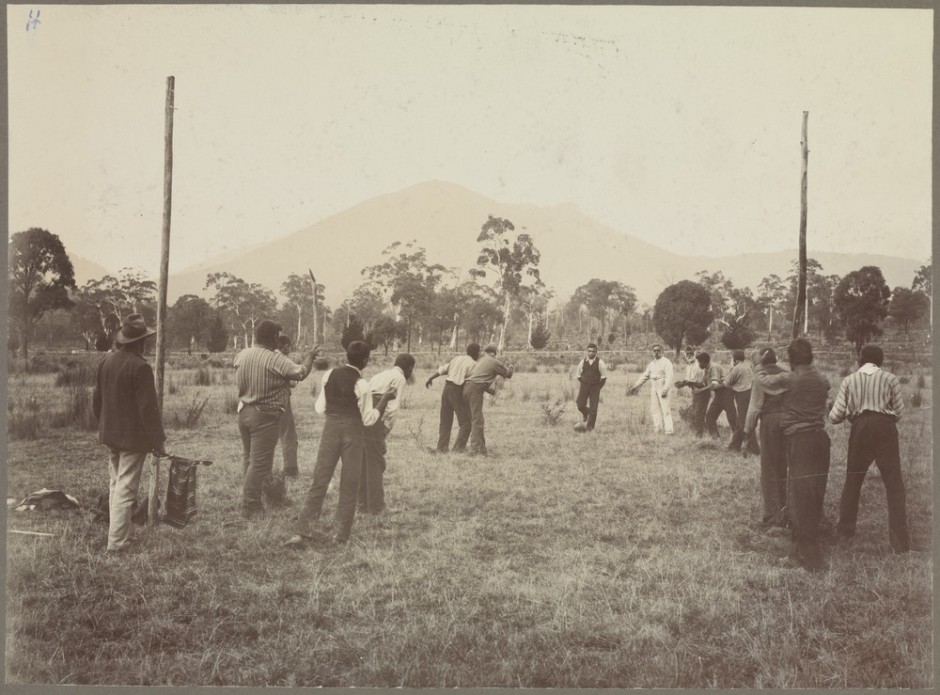

*Photograph of the Aboriginal Footballers of Coranderrk (1904) comes courtesy of the State Library of Victoria.