Twenty thousand souls were crammed into Hampden Park. Five times they leapt to their feet in wild delight as England crumbled under Scotland’s second half hammer blows. How those Scottish throats would roar! Nobody there on that windy afternoon in Glasgow would forget this glorious moment in Scottish football history. The final score was emphatic: Scotland 5 England 1.

He was there.

But not on the terraces.

He was down there on the pitch, in the thick of it, the crowd cheering him on. Playing on the right side of the attack, he could control a ball on the run and glide past a man with an ease that earned him the nickname ‘graceful.’ He had a nose for goal too. While he didn’t add to his tally that day, he’d previously scored four times for Scotland. If that wasn’t enough to make him famous in the football mad city of Glasgow, he was also a star of the all-conquering Queen’s Park club.

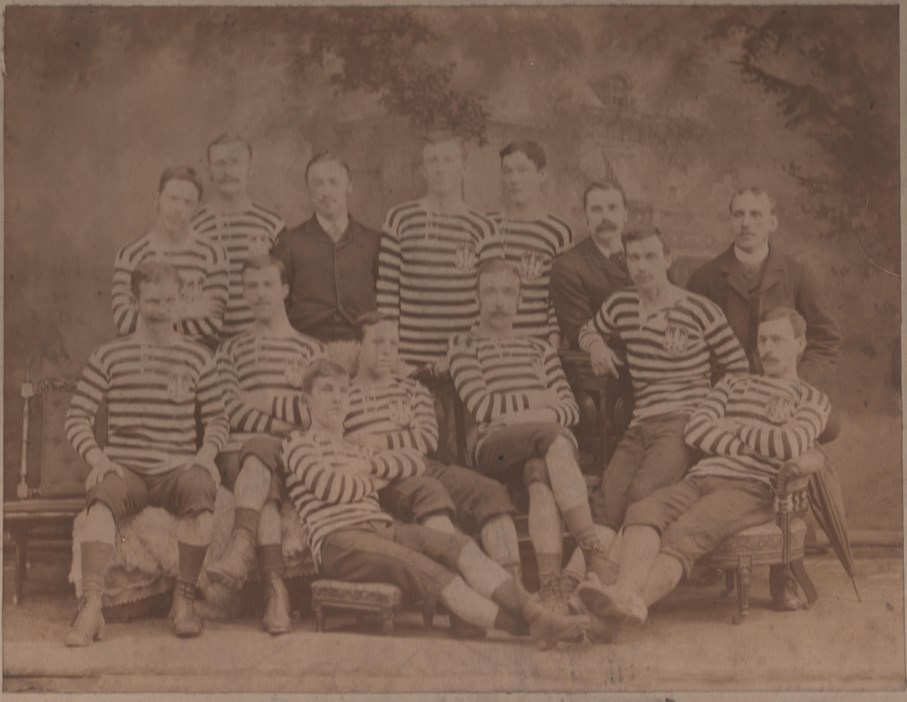

Queen’s Park Football Club 1882. Eadie Fraser seated up front. Photo supplied by Alex Cochrane

But that was before he got sick. Before the tearful farewells. Now the noise he heard wasn’t a rapturous crowd; it was the creaks and groans of the Ardmore’s hull as she struggled south through the swell. The Ardmore was sailing to a warmer climate, one that would heal him. He was heading to Australia.

On Saturday, 9 January 1886, Reverend Alex Miller of St Andrew’s Scots Church in Sydney received an urgent message requesting he visit a young Scotsman, newly arrived off a ship, who was gravely ill in hospital. Miller hurried off at once. At the Prince Alfred Hospital he was met by David Walker, the secretary of the Sydney YMCA. Walker had some bad news for him. The young Scotsman had passed away the previous day. When Reverend Miller found out the dead man’s name he was devastated.

Eadie Fraser!

This was terrible news. They had been childhood friends back in Glasgow. Eadie Fraser was one of the biggest stars in Scottish football. Miller began the solemn task of writing to Eadie’s family and sending home his personal effects, including a letter he had been composing to his sister on the voyage out.

Later that year a meeting was advertised in Sydney’s Evening News:

‘TO FOOTBALL PLAYERS.

Eadie Fraser Memorial Fund

for those that are interested

in erecting a MEMORIAL STONE

above the famous Queen’s Park player’

The meeting was chaired by Reverend Miller who spoke of Eadie Fraser’s renown as a footballer. There were the club triumphs for Queen’s Park and international appearances for Scotland. He put forward the resolution that it would be a ‘fitting and graceful tribute to his memory that a memorial stone be erected over his grave.’

The resolution was passed. A committee was formed and subscription lists prepared. It looked like the memorial proposal had momentum, yet funds were slow to come in. In March 1887, at a meeting of the Anglo-Australian Football Association in Melbourne, a letter from the Sydney association was read out requesting assistance in funding the memorial. No action was taken. At a later meeting in Sydney, Reverend Miller again appealed for donations.

What happened? Did the soccer community of Australia eventually raise some kind of memorial headstone for Eadie Fraser?

An unexpected mid-week day off presented me with a window of opportunity. I’m not sure why, but on that day I decided I would try to find Eadie Fraser’s final resting place.

* * * * *

There’s a spot marking Eadie Fraser’s grave on the map I have printed off the internet. Finding it should be a piece of cake.

Not so fast.

An old acquaintance once instructed me on the pitfalls of searching for someone in a graveyard.

‘You have to be respectful,’ she said. ‘You can’t just go in there stomping up and down like a billy-goat or you’ll never find what you’re after. You have to ask politely for their permission.’

‘So what if I don’t?’ I said.

‘They will play tricks on you.’

‘Like what?’

‘They make a mockery of your maps. They like nothing more than seeing you get hopelessly lost.’

It’s advice I should have heeded on my last cemetery jaunt. Armed with a 100 year-old map reference I trudged up and down a section of Waverley Cemetery for hours to no avail. When I got back to my car I couldn’t find my car keys. Talk about lost. I wouldn’t have made it home if I hadn’t taken the unusual step of bringing a spare set of keys with me.

Her final words on the topic were: Respect the dead and you won’t get lost.

So if I’m to have any hope of solving a 130 year-old mystery, it will pay to be respectful. This time my destination is Rookwood. And it’s a burial place like no other.

I’ve driven past Rookwood plenty of times but never actually set foot inside. It’s a brooding green presence that runs for miles on one side of busy Centennial Avenue. Nobody going about their business really notices it. By topology or some elegant chicanery of the designers, the graves and tombstones are hidden from view.

There’s a story or at least an urban myth about how Rookwood came by its name. In the early days, large numbers of crows inhabited the area. They reminded a local resident of rooks, the large black birds that gathered in ominous flocks around London. The resident wrote to a newspaper suggesting the name Rookwood and it stuck.

The site was chosen as being roughly midway between the townships of Sydney and Parramatta. In 1867 when the cemetery opened it was on the urban fringe. Now it’s almost geographically and demographically the centre of the metropolis. That old joke about the cemetery being the dead centre of town rings true at Rookwood.

I follow my phone map directions to the letter. Missing a turn means a long drive to the next entrance. Up ahead I see a sign on a low wall in big letters: ROOKWOOD NECROPOLIS.

I nudge the car over to the function centre and pull into the car park. They say Rookwood is one of the largest burial sites in the world and as I look across the vast expanse of graves and monuments I can truly believe it. I get out of the car, excited about the task ahead, a spring in my step almost. I check a big roadside map. The layout looks very different from the one I have printed.

They make a mockery of your maps.

I figure out the general direction I need to take and hang a left on Necropolis Drive.

The roads not far from the entrance gates are busy with traffic. People are looking for parking spots; a taxi drives past. All this on a weekday.

I pass a signpost for a Serbian Cemetery, an Assyrian Cemetery, then a Jewish Cemetery next to the Muslim one. It is evidence of Sydney’s multicultural present and its rarely acknowledged multicultural past. Further up on the left is the Independent cemetery. Such are the labels of the dead.

There’s a huge variety of trees here. I feel frustrated that I can barely name any of them. One I can identify is a Norfolk Island Pine that has a marked lean to it. The building near its foot just happens to be the Information Centre.

The clerk behind the counter looks up Eadie Fraser’s gravesite. She marks the approximate location on a visitor’s map and hands it to me. It looks nothing like my internet-produced map, which I toss in the bin.

Respect the dead and you won’t get lost.

I pass a florist. I guess I need to mark my visit somehow. Eadie Fraser was a man who proudly represented Scotland, so something blue seems appropriate. Unfortunately I forget the name of the purple-blue flowers I buy the instant I leave the shop.

I find the Presbyterian cemetery in the old part of Rookwood. When I get out of the car all I can hear is the rustle of leaves in the breeze and birds singing. There is no traffic noise. No buildings from the surrounding suburbs are visible; it’s just gravestones, monuments and trees for as far as the eye can see. I am reminded that the term necropolis means city of the dead.

Most of the graves here are from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and there are few signs of recent burials. It seems hardly any one comes by here these days. I check the map. A good twenty minutes and I should be out of here.

For reference, I have a section number and a grave number. Find section nine and it should be a cinch to locate the grave. On the ground, the map doesn’t quite look right. It appears my visitor’s map is more stylistic than cadastral. A few hundred metres away is an imposing stone structure, a chapel perhaps. I use it to get my bearings and make a few grid-like sweeps in all directions.

At times the numbers on the graves are sequential but on the next row the sequence will be out. When I struggle to read a number I put my fingers to the stone to figure it out by feel. What is the stonemason from over a century ago saying? Is it a three or an eight?

I glance at the headstones, hoping to catch the name Eadie Fraser. What would his plaque say? Eadie Fraser, the Queen’s Park star who once scored five goals in a Scottish Cup tie? Or maybe, Here lies Eadie Fraser, the Graceful Eadie, pride of Scotland. But alas, nothing.

“They make a mockery of your maps. They like nothing more than seeing you get hopelessly lost.” Searching for the grave of Eadie Fraser in Rookwood General Cemetery. Photo supplied by Paul Nicholls.

The search is frustrating. I get to within fifty of my number when the row of graves comes to an abrupt end in a patch of scrubby bushland.

The bushland is quite forbidding. It is unkempt and the undergrowth thick. I have read stories of red-bellied black snakes sunning themselves on the graves at Rookwood and I can imagine them feeling right at home here. I pull myself away from the bush and head back to the search.

I start walking faster between the rows and resist the temptation to step over a grave to make a shortcut.

Respect the dead and you won’t get lost.

There’s a marker in the ground that has sunk and shifted over the years and has ‘PRES SECTn 9’ inscribed on a rusted metal plate. I must be close. I pay sharper attention to the headstones. Nearby a kookaburra stands on the grass sentinel-like, its eyes fastened on something. It makes no sound. Did a kookaburra’s laugh ring out here the day Eadie Fraser was laid to rest? What would a Scotsman have thought on first hearing a kookaburra? Probably the same as a kookaburra hearing bagpipes I suppose.

Marker stone. “I must be close.” Photo supplied by Paul Nicholls.

My enthusiasm for the search starts to peter out. Every time I hone in on the number, the row of graves ends near the patch of native bushland.

Out of the blue my phone rings. An unidentified caller. I hesitate for a moment before pressing the answer button. There is no-one on the line. I scan 360 degrees to confirm I am still very much alone.

Despairing, I head back to the chapel and pull out the map again. The chapel is labelled: “Frazer Mausoleum.” I have a sudden notion of things being hidden in plain sight. The spelling is slightly off – Frazer with a “z” – but documents at the time weren’t always accurate. I decide to inspect the mausoleum more carefully. It’s a sandstone structure maybe ten metres high. None of the small windows have any glass in them.

Frazer Mausoleum. Photo supplied by Paul Nicholls.

I make a complete circuit and find no markings at all until I notice two sets of initials on brass plates set into the doors. The one on the left is “J.F.” while the one on the right is “E.F.” As in Eadie Fraser?

The wind has picked up and the light has begun to fade. A flash of lighting comes from dark clouds to the west. As it starts to spit I decide to head home.

But I still have one thing to do. I can hardly take my posy of blue flowers back with me. What living person would want flowers for the dead? I pass a tomb of a Fraser family (none named Eadie) and place the flowers in front.

Respect the dead and you won’t get lost.

I arrive back at the Information Centre just as it is about to shut. The woman at the desk gives me an email address and says if I ask they might be able to identify the grave.

* * * * *

At home I cranked up the research. It turns out the Frazer Mausoleum is the family vault of John Frazer, a wealthy merchant. When he died he was one of the richest men in New South Wales, and the mausoleum, built in 1894, is the biggest in Rookwood. The initials E.F. are for his wife, Elizabeth Frazer.

What of Eadie Fraser himself? To find out more I approached Scottish historian Andy Mitchell who has written extensively about Eadie Fraser on his website Scottish Sports History. Andy put me in touch with Alex Cochrane, a descendant of Eadie’s sister Maggie. It was Maggie that Eadie was writing his letter to just before he died in Sydney. Alex still has Eadie’s letters in his possession and was kind enough to share them with me.

Maggie Frances Fraser. Photo supplied by Alex Cochrane.

What is curious is that Eadie wasn’t even born in Scotland. His father, Reverend John Fraser, had moved from Scotland to Canada as a young man. Eadie, whose full name is Malcolm John Eadie Fraser, was born in Goderich, Canada on 4 March 1860. The family moved back to Scotland in 1861 where his father became pastor of the church in Cumberland Street, not far from The Gorbals district of Glasgow. The Frasers were a sporting family and the house became a popular meeting place for many Queen’s Park footballers.

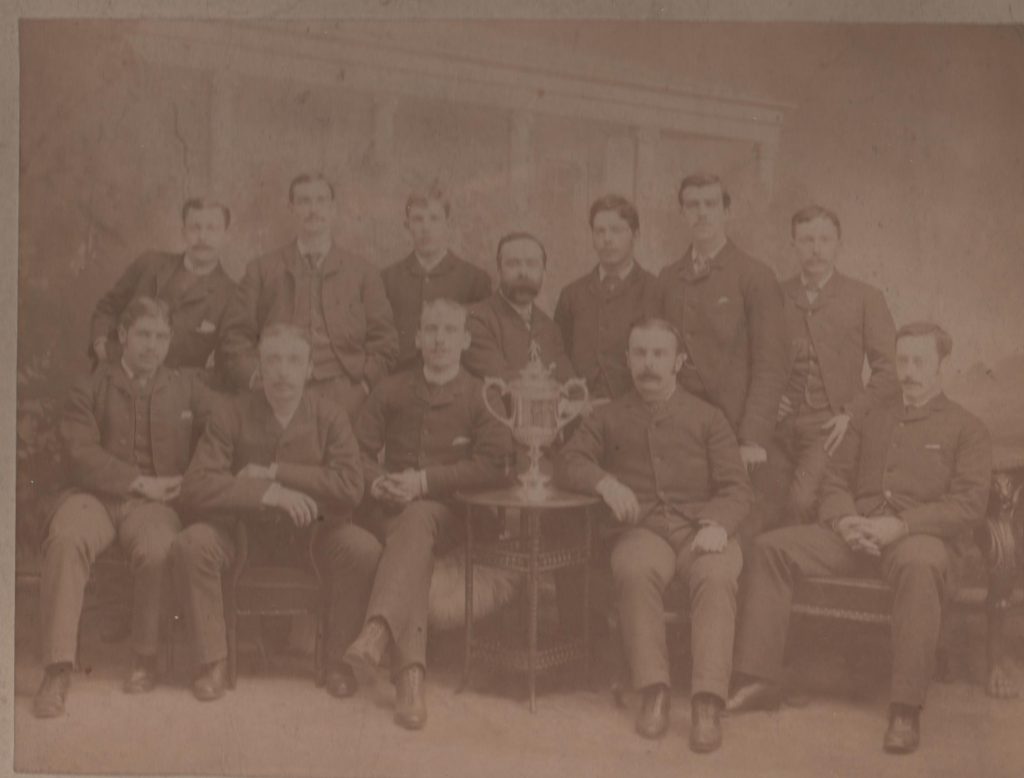

Fraser Siblings. Eadie seated left. Robert standing. Unidentified sibling seated right. Photo supplied by Alex Cochrane.

Eadie Fraser made his debut for Queen’s Park in the 1879/80 season and soon became a regular in the first team. He won Scottish Cup finals in 1881 and 1882, and in March 1880 gained the first of five Scotland caps in a 5-1 win against Wales. Eadie drew great inspiration from his older brother Robert who was also a talented footballer.

Queen’s Park Football Club 1881-1882. Eadie Fraser standing third from the left. Photo supplied by Alex Cochrane.

Club football in Scotland was still an amateur pursuit and in 1884 Eadie had no qualms about accepting a lucrative position in a firm based in the Niger delta in Africa. He left Glasgow just before Queen’s Park’s fifth round tie in the English FA Cup. Queen’s Park went on a great FA Cup run that year, losing 2-1 to Blackburn Rovers in the final. Many supporters felt that if Eadie had played, Queen’s Park might just have won it.

En route to Africa, Eadie’s ship stopped over at Madeira where his fame preceded him. While sitting at the roadside with some companions, a bullock cart drove slowly past. A man hopped down from it and said, ‘Is it Eadie Fraser? Man, man the last time I saw you was when your club the Queen’s Park were playing against the Dumbarton at Boghead in the cup-tie last year.’

Eadie’s football proclivities hadn’t deserted him on the voyage. When a rolled-up ball of paper blew across the deck he said: ‘The irresistible feeling of football seized me and I ran to kick the paper overboard.’ His shot ended up in the water closely followed by his unfastened shoe amid howls of laughter from his shipmates.

After a year in Africa Eadie became seriously ill with tuberculosis. He was sent back to Scotland where doctors advised him to travel to Australia where the climate would restore his health. Before he sailed, a benefit match in his honour was played between Queen’s Park and Glasgow Rangers. Bad weather kept the crowd down and only a small sum was raised. He left Glasgow as the only paying passenger aboard the sailing ship Ardmore on 19 September 1885.

It was a bittersweet farewell. The wives of the crew who dined on board with Eadie were in tears when it was time to go. Eadie’s brother Robert had also come aboard to say goodbye and as he was rowed back to shore Eadie went to call out but knew he was too far away to hear. Eadie settled down for the trip he hoped would save his life. He couldn’t get to Sydney quick enough.

The Ardmore was making good progress until five stowaways were discovered in the hold. The captain had to turn around and put them off at Cork. When they got underway again the wind had abated; the detour had cost them at least fifteen valuable days.

There was no hot water available and nearing the equator, Eadie took advantage of the warmer weather by having a cold bath. This triggered an episode that had him coughing up blood for days. Eadie wrote: ‘the poor old steward’s tears flowed copiously when he was carrying me into my bunk. He said he thought he would never get me in alive.’

The Ardmore docked in Sydney on 3 January 1886 and Eadie was immediately taken to the Prince Alfred Hospital. A few days later his health improved enough for him to continue writing his letter. He noted: ‘the harbour is most magnificent, it is the finest in the world.’ He also felt he was on the mend: ‘I feel a great deal easier, and can take a jolly good supply of food now, so that is very encouraging.’ In his letter he mentions the concern shown by David Walker of the YMCA and how Walker was organising for him to spend time in the Blue Mountains when his health improved. Eadie also looked forward to an imminent visit by Reverend Miller.

Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, 1886. Photo supplied by Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. Photographed by Charles Bayliss.

But Eadie wouldn’t live to see the Reverend. He died less than a week after arriving in Sydney. I desperately wanted to know about the funeral and who, if anyone, was at the graveside. I reviewed all the newspaper articles and pieced together some details.

Eadie was buried the same day Reverend Miller arrived at the hospital. His body was taken to Rookwood where Miller performed the service according to Presbyterian rites. The small band at the graveside were: Reverend Miller, David Walker of the YMCA, Captain William McVicar of the Ardmore and Hugh Cochrane, the ship’s carpenter. It was a hot summer’s day and the mourners would have been perspiring as they removed their hats and solemnly recited the lord’s prayer as the casket was lowered.

Back in Glasgow, The Reverend W.W. Beveridge, himself a former football player, received a letter from Miller ‘telling of the melancholy death of Eadie Fraser.’ Beveridge described Fraser as ‘one of the nicest fellows and ablest forwards who ever adorned Scottish football’ and ‘we cannot but mourn over the fair young life which has so sadly gone out into death’s darkness.’

The Athletic News remarked that ‘The news of his death has created profound regret in Glasgow, where he was well known, and had many friends.’

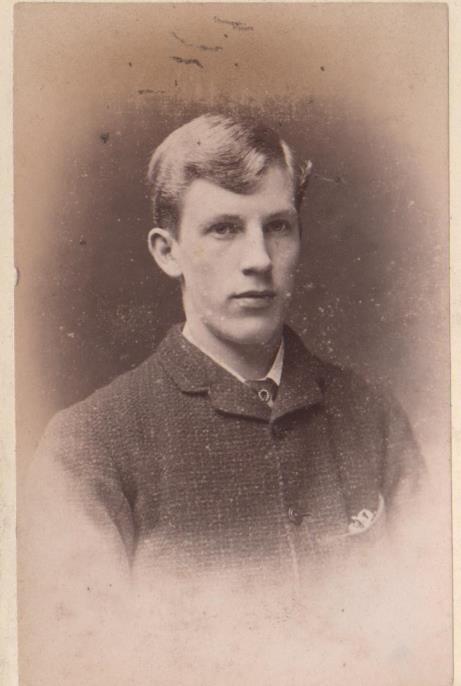

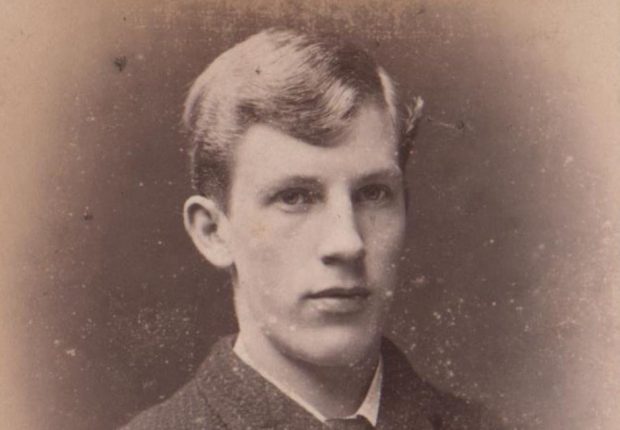

Eadie Fraser. Photo supplied by Alex Cochrane.

* * * * *

Later I received an email from the Rookwood Information Centre. Attached to it were two photos of unkempt bushland. The text of the email contained the following detail: There is no headstone.

Eadie Fraser’s resting place is the bushland that I kept bumping into on my search. The team at Rookwood marked the location with a card on a metal stake. It is proof the early soccer fraternity in Australia never managed to raise enough funds for a headstone.

The final resting place of Eadie Fraser. Photo supplied by Rookwood General Cemetery.

For all the good will in the world, there was a dearth of cash to splash around. It highlights the lack of visibility of Soccer in Australia, which was still very much in the shadow of Rugby in Sydney, and Australian Rules football in Melbourne.

There is a marked contrast between the case of Eadie Fraser and that of Robert Seddon, captain of the English rugby team, who drowned on the Hunter River during the 1888 tour of Australia. Of course, rugby had a higher profile in Australia, made doubly so by what was the first tour by England. A substantial memorial stone was erected to Seddon at the West Maitland cemetery, with donations coming from many organisations, including soccer’s governing body, the Southern British Football Association.

As a football historian I have long noted the existence of strong and close-knit Scottish communities, not just in mining towns but in Australia’s cities as well. Soccer clubs with Rangers, Thistles or Queen’s Park in their name are testament to this. Indeed, the Sydney club, the Caledonians, required their members to be either Sottish born or have at least one parent born there. It was a club that would have been eager to recruit someone like Eadie Fraser. In almost every centre where soccer was played an ‘England versus Scotland’ representative fixture was an annual highlight.

In the context of Australia’s immigration history though, the Scots as a community rarely get the same recognition as the Irish, Italians, Greek and Chinese for example. Perhaps it is because they assimilated so easily that they became less visible as a group.

But after spending time wandering among the graves of Mackenzies, MacIntoshes, Frasers and Kerrs, while searching for an almost forgotten football star from a distant era, I couldn’t help getting a sense of Australian Scottishness. Seeing some of the more elaborate headstones and family vaults shows that many had made good in their new country, and some had become leading citizens. Of course, it didn’t apply to all. As in any diaspora, there were people who didn’t fare as well or who died before they could establish a foothold. Among them is Eadie Fraser, whose unmarked grave lies in the native bushland at the end of the Presbyterian section of Rookwood Necropolis, near where the kookaburras laugh.

Paul Nicholls wishes to acknowledge Alex Cochrane, Andy Mitchell and his website Scottish Sports History and the Queen’s Park Football Club history website in helping him tell the story of Eadie Fraser.

thanks did not know about that story

What a marvellous piece of detective work and a splendid story, Paul. I knew nothing about the man, so all this is new to me. I’m down to talk to the 4th International Football History Conference at Easter Road in June on the Scottish influence on Australian football—footy as well as soccer. It is just a pity that I cannot add your man to the list of those who contributed.

Excellent research and very moving piece. Well done