They call him Judy: The day an Australian coal miner challenged English football supremacy

Sydney, 1925…

They call him Judy.

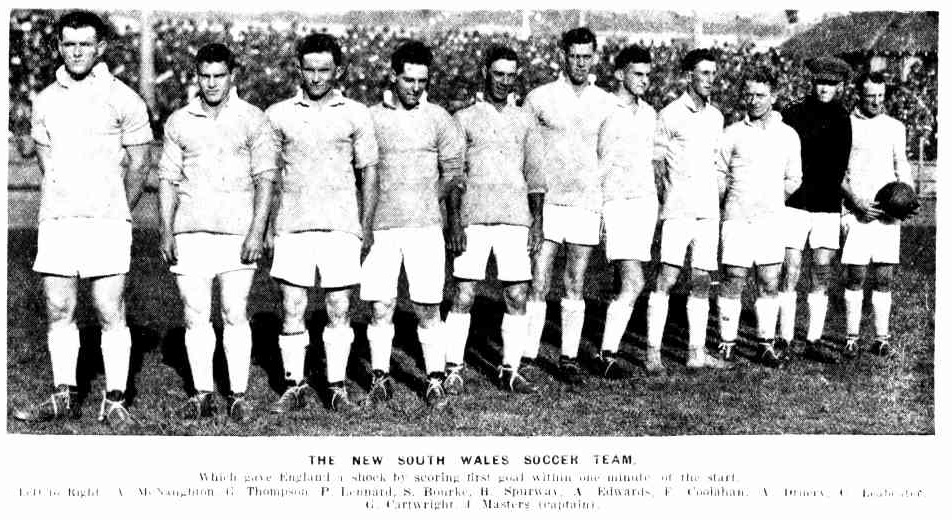

Dressed in a football jersey the colour of the pale blue sky outside, he is nervously pacing the dressing room under the grandstand of the Sydney Showground. Nearby his New South Wales teammates chatter quietly amongst themselves, all bar one in the unmistakeable accent marking them as Australian born and raised. They understand the task in front of them is a formidable one.

Their opponents have won all six matches on tour so far, scoring at a rate of nearly seven goals per game. They have conceded just the one goal, a dubious penalty.

But James William “Judy” Masters knows that New South Wales have some things in their favour. They are the strongest soccer football state in the Commonwealth of Australia. The players know each other well. Dog trials held on the bone-dry, bouncy pitch the previous weekend has made the surface uneven which should disrupt the passing game of the superior opposition.

The players are hopeful of a good turnout but as nervous rugby league officials have strategically staged their showpiece clash between New South Wales and Queensland at the Sydney Cricket Ground right next door, the size of the crowd at the football match is uncertain.

Above the strains of the Westmead Boys Home Band the players can hear the murmur from the spectators outside. There is a sense that something extraordinary is about to take place. The noise of the crowd hums and crackles like the air in Sydney just before a southerly buster hits.

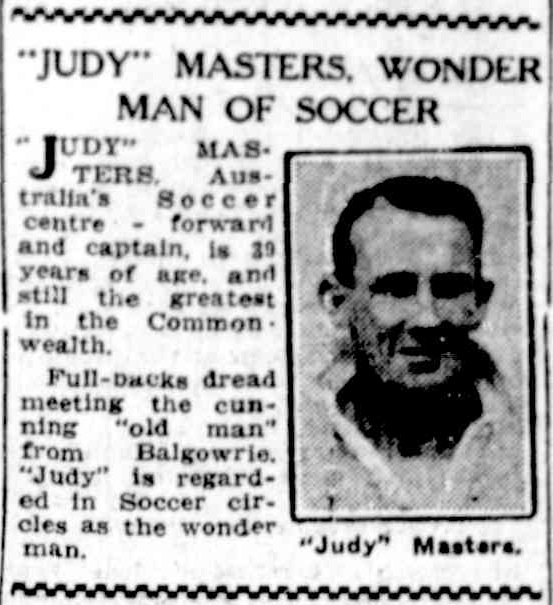

As Judy Masters leads his men out of the dressing room he knows he has their unwavering support. He is a legend of the sport of football in Australia. Not only is he the greatest centre-forward the country has produced, but having survived the horrors of Gallipoli and the trenches of the Western Front, Masters has the respect of players and spectators alike. Even his opponents know who he is.

The sight that greets the New South Welshmen as they step onto the field is like something out of a dream. The ground is jam-packed. The grandstands are so full that people are standing in the stairwells. A man has lashed himself to a railing of the grandstand so he won’t fall. People are perched on the roofs of surrounding buildings. The crowd is bigger than anyone has imagined, at least 50,000 before the gates were closed and officials stopped counting.

It’s no wonder, as early hour trains have been bringing spectators in from all over Sydney and outlying areas.

In Newcastle harbour, one hundred miles to the north of Sydney, at least one ship has been left without a crew as all on board have made the trip southward. The trains that leave Newcastle are crammed with fans supporting their own local players in the New South Wales side; men such as Peter Lennard and Ken McNaughton.

Supporters from the Illawarra district south of Sydney, have also made the trek up. In Tommy Thompson and Judy Masters they have their own favourites.

For 1920s Australia this crowd is as cosmopolitan as it gets. There are accents from all over the British Isles. There are Europeans drawn from ships’ crews berthed in Sydney. And amongst the mainly white faces are some of Sydney’s Chinese community who became supporters of the game after a visit from their countrymen two years before, a visit the nation’s strict immigration laws known as the White Australia policy almost halted.

When the cheer for New South Wales dies down, there is silence as the crowd crane their necks towards the grandstand for a glimpse of their opponents.

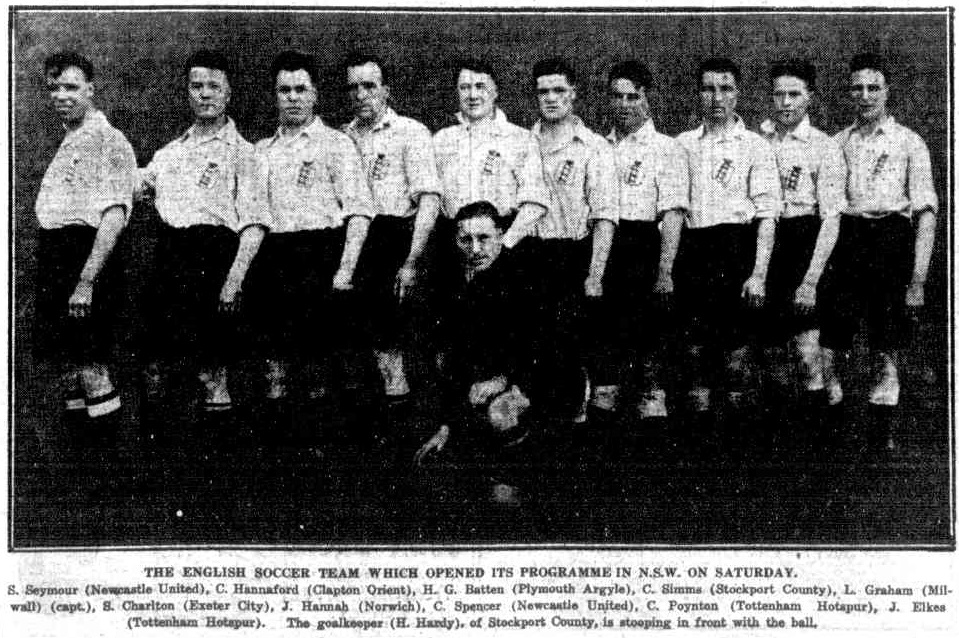

Then ten white-shirted men and a yellow-shirted goalkeeper, led out by skipper Len Graham, emerge onto the arena. Embroidered on their left breast is a crown over three lions.

This is England.

The crowd let out a deafening roar that shakes the grandstands like an earth tremor and reverberates into folklore.

The English Football Team that played NSW on May 30, 1925. Source: The Referee, June 3, 1930.

Football fans in Australia have waited years for this very first English team to arrive on home soil. For recent British immigrants there is an outpouring of genuine emotion. These English professional footballers are the embodiment of their favourite game, the sport of the working man, the sport of the masses back home. More than just pride, there is a nostalgia in this massive cheer. Never has the British Empire felt so real. Never has Australia seemed so much a part of it. Here in Sydney, twelve thousand miles from the factories of Birmingham and Manchester and Liverpool, the dormant heartbeat of a fading Empire has sprung to life with a thumping boom.

New South Wales supporters draw a deep breath when they see the teams line up. England are muscular and athletic while the team in sky blue looks puny in comparison. The locals are amateurs who work at full time jobs. What chance do they have against a team of hardened, professional footballers? And at 33 years of age, Masters, the coal miner, is surely past his prime. The grim reality on this clear and cool winter afternoon is that New South Wales will surely be slaughtered.

Photo of the NSW Football Team that played England on May 30, 1925. Judy Masters on the right holding the ball. Source: The Sydney Mail, June 3, 1925.

It is 3:15 pm, on the 30th May 1925.

The referee, Mr. Wright blows the whistle. New South Wales kickoff. Just 90 seconds later Judy Masters runs to meet a cross and heads it into the bottom corner of the English goal.

The crowd erupts.

England scores a goal against New South Wales in front of 50,000 spectators at the Sydney Showground, May 30, 1925. Source: Sydney Mail, June 3, 1925.

England soon equalised but remarkably Masters put New South Wales ahead again when he sprung the off-side trap to score a second time. England made it 2-2 by half-time and scored the winner just after the 80th minute. England won all 25 matches on their 1925 tour of Australia. This was the closest they came to tarnishing their perfect record.

“Judy” Masters Wonder Man of Soccer. Source: The Labor Daily, May 27, 1930.

Judy Masters was a Wonder Man of Australian Soccer. He played over 400 club and representative games. He scored 351 goals and never received a caution from a referee. He died on 2 December 1955 from black lung disease (pneumoconiosis) brought on by four decades of breathing in coal dust. He was 63.

Feature illustration by Martin Stainforth of the second match between New South Wales and England played on June 6, 1925. Published in the Sydney Mail, June 10, 1925.

Great story — and superbly written article, Paul!

nice one Paul!