Loved and loathed in almost equal measure, script doctor Robert McKee’s book, Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Storytelling, sets out guiding principles on how to write a well-structured and dramaturgically coherent film script. It is a text that aims to bring method to the supposed madness of the scriptwriting process.

Also loved and loathed in almost equal measure, Portuguese football manager Andre Villas-Boas is a character, a protagonist, who aims to conquer the often chaotic, tradition-bound world of football. He attempts to do this by applying method to the madness of both on and off-field activities at the football clubs he has managed.

As with McKee, AVB — as he is commonly known — has inspired an army of fans and disciples.

The recently sacked Tottenham manager’s admirers are convinced by the rightness of his method in the face of an archaic establishment and the protests of the individuals threatened by his, mostly self-professed, new ways of thinking about the game.

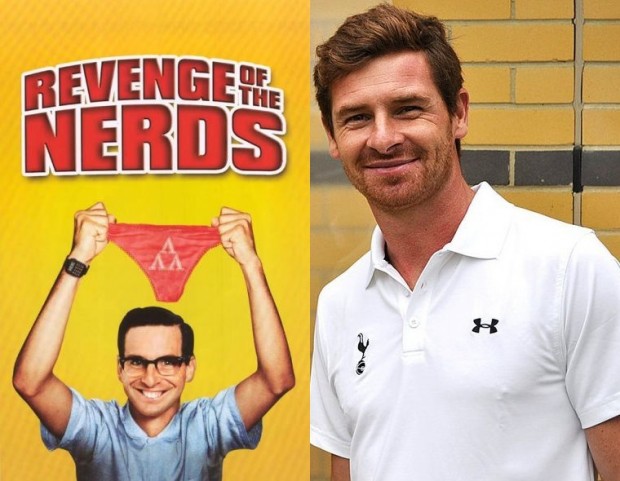

AVB has most endeared himself to a younger generation of football fan; educated, maybe a little bookish, and brought up on the DIY football management fantasies of Football Manager, Fantasy Premier League and the FIFA series of video games. These fans see something of themselves in AVB. They identify with his nerdish, continental suavity, as well as his status as an outsider in the clubby, cozy world of European football.

He is a compelling character, with a unique backstory in football. A maverick without the boorishness that term sometimes implies, AVB beautifully fits the mould of McKee’s protagonist, as outlined in Story.

“The Protagonist is a wilful character.”

A certain youthful pluckiness is evident in AVB’s climb up the ladder from being Sir Bobby Robson’s dossier boy at the age of 17 to being among Europe’s managerial elite by the age of 33, when he won the Portuguese cup and league, and topped it off by winning the Europa League with Porto.

It is still very unusual, though not unheard of, for a high level manager to have never played the game at even a moderately respectable level — look at Gerard Houllier, who just like AVB, never had the talent to play professionally. The usual path for a professional coach or manager is to progress from the rank of professional player, with maybe an assistant coach assignment or two and a smattering of coaching badges thrown in to round off and polish the CV.

The fact he did not come up through the usual route has left many ‘football people’ questioning his credibility, as Daily Express football columnist Mick Dennis tells it: “… behind AVB’s veneer of studiousness and his confident air of knowing a lot about the game, he was a man promoted too quickly and too far without having ‘paid his dues’ as a player or by coaching at lower levels.”

AVB’s rise demonstrates the type of willfulness which propels classic ‘fish out of water’ film scenarios that are the staple of so many Hollywood films. To succeed, he must be a man of will because his character make-up solicits ready opposition from establishment figures.

“The Protagonist has a conscious desire.”

Like any football manager, AVB’s conscious desire is to win major titles with his team, and if possible, while playing football the “right way”. One of the things that makes him such a compelling character is his conscious embrace of a football “philosophy”.

Unlike the classic Scottish pragmatism of Sir Alex Ferguson (possibly informed by the philosopher David Hume and the Scottish “common sense” school of rationalist thought), AVB’s thinking is along far more idealist “continental” lines, with direct links to his “father figure”, Sir Bobby Robson.

Of course, Englishman Robson is among the few British managers to have a successful career in both British and continental football, having spent about a decade at clubs in the Netherlands (PSV), Portugal (Sporting and Porto) and Spain (Barcelona).

While the other Robson protégé, Jose Mourinho, has become successful by embracing a ruthlessly pragmatic football philosophy, AVB has, naively in the eyes of some, insisted on trying to create teams that dominate opponents through possession and playing a quick-passing style. This, too, has set him up to be criticised by footballing conservatives and pragmatists.

“The Protagonist may also have a self-contradictory unconscious desire.”

Could this be AVB’s weakness, his ultimate undoing? A need to prove himself as belonging in a world whose inhabitants still view him as an interloper?

His rivalry with one-time friend and colleague Jose Mourinho may provide the antagonistic thrust which either propels him to success or condemns him to defeat. In a classic Cain and Abel trope, AVB and Mourinho are like two brothers fighting for the love of the absent father (Robson), one choosing the path of light, the other choosing the road of darkness.

Mourinho has overcome his own scarce playing history to become a leader and father figure to his players.

In a recent match between Arsenal and Mourinho’s Chelsea, the Arsenal playmaker Mesut Ozil expressed his feelings about his former Real Madrid boss:

“I gave my jersey to Mourinho because he’s the best coach in the world and I love him like a father.”

AVB has yet to inspire this level of respect and admiration among his players. In fact, AVB’s relationships with players have often seemed to be the biggest obstacle to his achieving success. This is perhaps highlighted by quotes like this, given in an interview AVB conducted with university student Daniel Sousa:

“Things have become too easy for football players: high salaries, a good life, with a maximum of five hours work a day and so they can’t concentrate, can’t think about the game.”

The almost comical story that emerged following AVB’s sacking from the Tottenham post about Emmanuel Adebayor’s beanie perhaps exemplifies the sort of animosity that exists between AVB and his players. The story goes that Adebayor (not known as the easiest character to get along with in world football) refused to remove his beanie when requested by AVB, leading to the Togolese striker being cast out of AVB’s plans at Spurs.

It is difficult to know how true the story actually is, but it illustrates the willfulness of AVB’s character, as well as his flawed abilities as a man manager. Could his self-contradictory unconscious desire be to demonstrate his superiority to players because he could never be a player himself? That for all his philosophy, the psychological aspects of dealing with real, difficult humans is what stands between him and the success he so craves?

If only football was a video game…

“The Protagonist has the capacities to pursue the object of desire convincingly.”

His success first at saving Portuguese battlers Académica de Coimbra (certain irony in that name too) from relegation and then at Porto showed he can win and that he can take a team to major titles.

AVB is not short of admirers. He is smart, driven and talks a fantastic game. And while his run-ins with players and club bosses — Roman Abramovich at Chelsea and Daniel Levy at Spurs — have ultimately brought him undone now at two clubs. He is capable of inspiring the devotion of some players, for example, former Spurs star Gareth Bale, who credited AVB with making him a better player.

What makes AVB a compelling protagonist is that we are not altogether sure that he is not capable of pulling off a major achievement one day with a big club. But at the same time, we’re also not sure if he is just a chancer, a character who has somehow moved above his station in life through a combination of scam, sham and luck.

“A Story must build to a final action beyond which the audience cannot imagine another.”

At what point along the AVB story arc are we? We are certainly at a critical juncture, which is possibly leading into the third and final act in which our protagonist must prove his bona fides beyond all contention, or spectacularly crash and burn trying.

We have seen him rise from obscurity, the young man as an unlikely outsider in the big, bad, cynical world of football. The first act concludes as he takes his bow at Porto, exiting as domestic league champion as well as Europa League victor.

We see him follow in the footsteps of former friend and now bitter foe Jose Mourinho, as he takes the reins at Chelsea under the capricious gaze of Russian oil czar Abramovich and tries to overhaul an ageing and declining team.

This is our protagonist’s troubled second act arc.

He suffers his first major setback when he is sacked by Chelsea. But resolute and wilful character that he is, he grabs a second chance to achieve his dream of success in the big-time of the EPL, this time with perennial underachievers Spurs. But, alas, it’s not to be, as what appears to be a fatal flaw in his genius make-up — the inability to control the big-names in is dressing room — once again rears its head.

So now we head into the third act.

Do we see our flawed protagonist emerge elsewhere to finally fulfil his potential and claim a major title, possibly even a Champions League win with a rank outsider, beating his great foe Mourinho in the final? Or do we witness a less conventionally triumphant outcome for AVB, where he goes to a small club and works his magic in a more subdued but satisfying manner? Does he finally find peace with himself by no longer chasing the big game and settling into the mundane existence of a mid-table manager at a university town in Portugal, back to where it all started with Académica de Coimbra?

“The Protagonist must be empathetic; he may or may not be sympathetic.”

AVB is a complex character; an outsider who is now on the inside, he carries with him the confidence and self-doubt that marks the ‘self-made man’. His prickliness and perceived arrogance put many people off, while his earnestness and idealism endear him to just as many.

We’ve yet to see the end of AVB. He’s sure to pop up somewhere soon, and when he does, you can bet it’s going to be a riveting third act, even if the script — along with AVB — has so far been stuck in development hell.