Soccer has trouble remembering itself.

This failing leaves it open to accusations of foreignness and unbelonging, accusations levelled from without and often complacently accepted from within. One of the more curious moments of amnesia in the game is its failure to acknowledge the soccer Anzacs – the soccer players who fought in both World Wars. The Caledonians in Perth, for example, lost many of their champion players during World War One, but the club holds no special place in the official history of Australian sport. Tiny Irymple, near Mildura, lost five of its players. Anzac Day is instead dominated by Australian Rules and to a lesser extent rugby league, which celebrate and memorialise their fallen heroes in an annual Anzac Day clash.

The tireless work of Kevin Sheedy and RSL President Bruce Ruxton in 1994 to set up the Anzac Day match is part of the legend. “How do we grow the game as well as remember an area of society that needs recognition?” wrote Sheedy, “We needed something to bring us together, not tear us apart. We proposed the idea of a game on Anzac Day that would celebrate the spirit of the diggers.” Amid the hubbub of the NRL and AFL Anzac football commemorations, soccer will gaze in wonder from the sidelines about where, if at all, it fits in the picture.

In a competitive marketplace for football, soccer’s culture of forgetting has left it open to broadsides and backhanders from other football codes. In May 2013, Sheedy, at that time a temporary immigrant from Victoria to New South Wales, opened another of his many propaganda fronts via an infamous remark about the relationship between soccer and immigration. As coach of the new AFL franchise Greater Western Sydney Giants, then in its second ever season, he was feeling the pressure after a 135-point battering from Adelaide in the first game at their ‘home’ ground, the Sydney Showgrounds. A paltry crowd of 5830 watched the dismal performance. Clearly frustrated, Sheedy asked for patience. “We don’t have the recruiting officer called the immigration department recruiting fans for the West Sydney Wanderers”, he said. “We don’t have that on our side.”

A missionary in a foreign land, Sheedy’s jibe at soccer was an expression of his own need for legitimacy and desire to belong. And his team kept losing, week after week. And few people were turning up to watch them lose. Derisory crowds of 6000 (for a game that usually averages over 30,000 wherever else it is played in Australia) suggested that this latest episode in Victorian cultural imperialism was struggling to make an impact in its target of Western Sydney.

Meanwhile, Western Sydney Wanderers, an A-League franchise in its inaugural season had achieved remarkable success on and off the field, winning the Premiership and losing the Grand Final. Despite Sheedy’s suggestion of their unbelonging, the Wanderers were playing to packed crowds at Parramatta Stadium, some of them full houses.

Sheedy’s ‘immigration department’ comment implied that soccer was having an easy time because of the number of immigrants settled in the western suburbs whereas his ‘Aussie’ game was flailing because it did not have the ready-made market – something of which the AFL was fully aware prior to establishing the franchise. Ironically, Sheedy’s claim was made around the same time that Greater Western Sydney Giants had successfully lobbied for government assistance in attracting migrants to the club. Some would be excused for seeing a classic case of projection.

Whatever might be made of the psychoanalytic reading, what is clear is that the Victorian imperialist had inverted logic and history and turned the locally embedded game into the foreign one while promoting his imported culture as the one that truly belonged. His sense of belonging was based not on felt inclusion or “terrains of commonality” but on imperial desire and mythological projection. To be fair to Sheedy, he was not the first to make that mistake. Nor will he be the last. Soccer’s history and cultural importance in Western Sydney runs farther back than many realise.

Someone who should know better, soccer reporter Michael Lynch, recently deployed the immigrant trope in arguing that the Asian Cup will be a decent consolation for Australian soccer’s missing out on holding the World Cup. “The stadia are there, and the immigrant population to help build the crowds is here, too. Let’s hope they, along with the locals, turn out to show FIFA what might have been possible.”

It’s as if the Sheedy moment and its aftermath had never actually happened.

Those who doubt the long-term embeddedness of soccer in Sydney would do well to study the case of the Granville Magpies. The Magpies were a strong club within a flourishing Western Sydney soccer culture in the early 1900s. The club continues today in various forms, and represents one of the many historical elements upon which the present support for the Wanderers rests.

The Magpies story is also an Anzac story. Like many of the soccer clubs established before the First World War, the Magpies contributed to the war effort. Seven of the twelve players pictured in the 1914 team photograph went to the front. In total 17 out of the 1914 Magpie squad of 22 players could “be accounted for as having done or are doing their bit for King and country in foreign parts.”

Reading left to right. — Front Row: *J. W. Masters, E. Mobbs, *W. E. S. Dane. Second Row: *H. Wheat, J. Kiordan (chairman G. and D.F.A.), R.H. Moore (captain), T. Nobbs (patron), H. Hoffman, J. Tillman, L. Gill. Third Row: A. Epps (hon. sec. G. and D.F.A.), *R. Fairweather, J. W. Cottam, F. M. Smith, J. Davis, E. J. Doherty, F. Robertson (hon. sec). Back Row: F. Waddell (manager), A. Peaty, S. Hilder, *Sergeant-major F. Doherty, P. T. Williams. Asterisk denotes those at the front.

One of the players pictured, JW Cottam, was killed in the fighting. The military circular announcing his death commented that he was a ‘prominent soccer player’. An extended notice of his death in the Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate read:

The deceased soldier, John Willie Cottam was a great favorite in this district. He was a noted Soccer footballer, and many members – and high officials, too – of the G. and D.F.A. have this week quietly and unassumingly bowed their heads as they heard the sad news. He was a prominent member of the redoubtable ‘Magpies’, and played centre forward in the team that won the double event – the Gardiner and Rawson Cups – in one season (1914), following it up in 1915 by again winning the Rawson Cup and only meeting defeat for the Gardiner Cup in the semi-final, in 1915. He also held an honor cap from the Sydney association. His only, brother, Private Albert Cottam, is 21 years of age, and is still fighting in France; He enlisted in November, 1915, was ill in Egypt, completed his training in England, and has been in the firing-line since November 10, 1910. He, too, was a footballer before enlisting, but was attached to the Parramatta Juniors, who won the Soccer medals in 1914.

Two of the family names in the team photo live on in the names of the Eric Mobbs Reserve, a present day soccer facility in Castle Hill, and the Cottam Cup, a Granville district knockout trophy that goes back to 1907. The earliest reference to the Cottam Cup is in 1920. The name was changed from the Rawson Cup after the war to commemorate John Cottam.

Another member of the Granville Magpies not pictured in the team photo also met his death at the front. The Cumberland Argus reported in 1917:

PTE. WILLIAM ERNEST BRICKLEY, of Clyde, killed in action. Soccer enthusiasts in the Granville district will regret to learn that Private W. E. Brickley, better known as Billy Brickley, paid the supreme sacrifice on the battlefield in France on 3rd May last. He was a prominent member of the old Magpie team and one of its best players. His poor old mother, Mrs. A. Brickley, who resides in Factory-street, Clyde, received word from the Defence Department on 3rd June that Billy had been reported missing on 3rd April. Then on 10th July she got further word that he was killed in action on 3rd May. The last letter she received from him is dated2nd May, the day before his death. He was then in cheerful mood and seemed pleased to let his mother know that after waiting anxiously for many months for a letter from home, he had just got a whole bundle of letters. He belonged to the 18th Battalion and left for the front in October last year. He went straight to France after leaving Australia? He was 28 years of age, was married, and leaves one child. His father died about two years ago. He was the youngest son and was born at Kendal-st. Clyde. He went to North Granville public school and afterwards was employed for years at the Clyde Engineering Co.’s Works and later at Messrs. Ritchie Bros.

Other men in the district also fell. The Cumberland Argus reported that the Granville and District Football Association carried votes of sympathy to Mr. Mills and family and Mrs Rea and family in the fate of their sons at the Dardanelles. The paper reminded readers that the “fathers of both these gallant boys were two of the earliest players of the Soccer game in the State, and are not yet forgotten by many friends they then made.”

SERGEANT WALTER E. REA. A promising popular Parramatta boy – at the time of his death 20 years of age – gave his life for his native land and for Empire, when Sergt. Walter E. Rea fell on the field of battle at the Dardanelles on May 24. The deceased soldier was the eldest son of Mrs. Rea, of Church-street, Parramatta North (widow of the late Mr. David Rea, a popular Parramatta citizen and footballer of 20 years ago). Sergt. W. E. Rea was grandson of the late Alderman John Saunders. He was an officer at the Parramatta North Methodist Sunday School for a time before he left. He was one of the first of the Parramatta lads to volunteer; and his high character and attention to his military duties soon won him promotion.

Close analysis on the texture of the language of the obituaries intimates the extent to which these men and the game they played belonged to their community. Soccer is celebrated as a central aspect of their social lives in Granville and Western Sydney, not a foreign or peripheral influence.

At war’s end, The Cumberland Argus reported on the return from duty of two of the Magpies in the team photograph.

Harry Wheat, the well-known Magpie player, returned from the war a week or two ago and visited Granville on Monday. He was captain of a Soccer team at the last camp he was at in England, where a competition was held amongst the different companies of soldiers. The final game was played on the Saturday prior to his leaving for Australia, and his team scored a good win. Ned Doherty, the well-known full-back of the Magpies, was also a player.

Like many of the Australian troops, Wheat and Doherty had played a fair bit of soccer while in the army and upon their return expected to resume their careers with the Magpies, which they duly did. They certainly would not have expected to have been thought of as migrants and foreigners in their own country.

Almost a century on, would Wheat and Doherty – two honest, working class Australian men – have expected their game to be seen as a curiosity? One can only wonder what they would have thought of a troublemaking migrant from far-away Victoria treating their game as a foreign influence, one played and supported by people who needed to be ‘channelled’ and ‘brought’ illegitimately into the region by a government department. Indeed, the game they played and nurtured in Sydney’s west is nothing other than a rich and established local culture of 130 years standing.

A similar story of belonging and Anzac commitment can be found in relation to another Western Sydney club. The Lidcombe Methodists also provided a good number of soldiers in the Second World War, three of whom did not return. The Cumberland Argus contained the following report early in the war:

The inevitable has happened. Lidcombe Methodist team has been forced to draw out of the first grade competition owing to five of its members joining the AIF. Regrettable as it may seem, there is the consolation to its leaders that its eligible members have responded to the call of Empire.

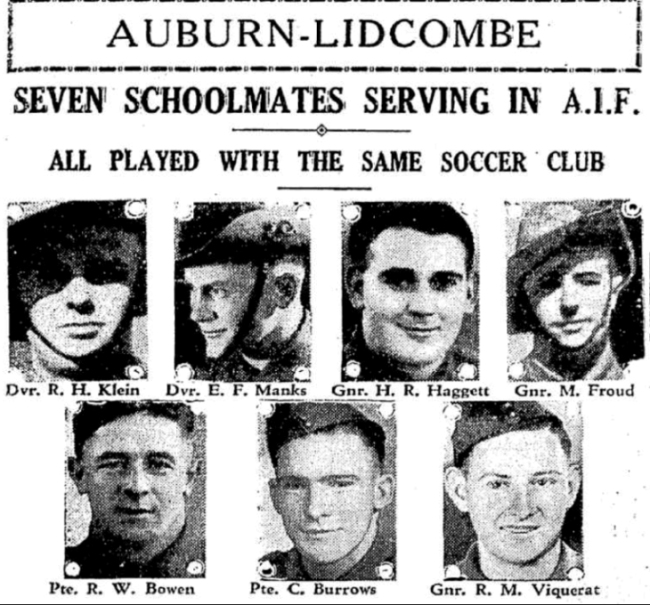

Little was the writer to know that many more from the club would enlist over the next few years. In October 1941 The Cumberland Argus told the story of how seven school friends and teammates ‘together since kindergarten’ joined up as a group. Again, these young men were locals, embedded in their communities, leading typical, ordinary lives and working in typical, ordinary jobs.

Together since their kindergarten days, these seven Auburn soldiers are all serving overseas with the AIF. Mrs. Haggett, of Simpson-street, Auburn, told their story this week; She is the mother of Gunner Haggett. ‘These boys grew up together and looked upon my house as their own,’ she said. ‘They all went to Auburn North School together and played with the Lidcombe Methodist Soccer Club.’

‘Bunny’ left with the first AIF contingent, and the others resolved to follow him, which they did. ‘All the boys but mine have met him, but my boy wanted to see him, perhaps most of all. Once in the Middle East, he missed him by a few hours:’ Private Burrows has been through every AIF campaign, and was last heard of in Palestine. Gunner Viquerat and Gunner Haggett went to Syria, but their present whereabouts is unknown. Driver Manks is in Malaya, and Private Bowen, Driver Klein, and Gunner Froud are in Syria. Before enlisting, Private Burrows was employed by the Australian Gas Light Company, Gunner Viquerat was a driver for Schweppes, Gunner Haggett was an upholsterer, Driver Manks was a plumber, Driver Klein worked at the Australian General Electric Company; Gunner Froud was at the Advanx Tyre and Rubber Company, and Private Bowen was employed on the railways.

‘All the lads write to me regularly, and now they’re looking forward to the day when they stage their big re-union,’ said Mrs. Haggett. ‘But there’ll be a bigger, re-union when they get back to Aussie,’ she added, wistfully.

A member of the Auburn Red Cross, Mrs. Haggett belonged to the Auburn Women’s Voluntary Services. The mothers of the other boys were also members of the Women’s Volunteer Services.

In 1946 The Cumberland Argus contained a follow-up piece which told that ultimately 16 players from the club served in the war and three of them – Driver Joey Manks, Allan Moss and Driver Arthur Thomas – did not return. Nonetheless, the surviving players fulfilled a vow they made to each other to reform the team and play again. No doubt some thoughts for their fallen teammates were part of the process of renewal as the Auburn District Soccer Football Club.

In an article titled ‘The Pledge has been Fulfilled’ in The Cumberland Argus, one of the players reflected on the new club. “We’re not quite as good as we were – after all, six years away from the game does mean something”, said the player. “But we’ve never been defeated by more than two goals.” The player also spoke highly of club president Perce Bunyan, who he said had “rounded up the players, helped finance the club, and got it going again. Only for him we would not be where we are to-day. All the boys appreciate his work.”

As is the case with the tale of the Granville Magpies, the power of this story lies in its ordinariness. These were everyday, predominantly working-class Australian men thrust into war and whatever misery, heroism and solidarity they might have encountered in their time in the armed forces. Among the nourishing memories of family, school and friendship they each had soccer as a game to unite them, sustain them and provide them something to which they could return and ritualise if they were fortunate enough to come home in one piece.

Kevin Sheedy’s remarks angered the soccer community because they harked back to days where soccer was dominated by newly arrived migrants from Europe. They re-opened the old ‘wogball’ wound. What Sheedy and some members of the soccer community forgot (and still forget) was that a strong soccer culture has existed since the late 19th century, well before the large-scale post-war immigration programs. For the soccer Anzacs – Harry Wheat, Ned Doherty, and the Lidcombe Methodists – soccer was there before they left and it was in place when they returned to where they belonged. Soccer is indeed undergoing a boom period in Western Sydney, but it is just one of many peaks in a 130 year-old history. Long has soccer been a vital sporting mainstay of Western Sydney.

Ian Syson would like to thank Joe Gorman for his assistance in putting this piece together.

For further ‘Soccer and Anzac’ reading we recommend this piece from Ian Syson’s Neos Osmos blog.

A well researched article which reinforces the great history of football in the Western Suburbs.

Certainly, the FFA and the state bodies do little to identify with ANZAC Day which does allow cheap comment from prejudiced people like Kevin Sheedy .

However, Ian Syson appears oblivious to the fact that football has experienced this sort of prejudice for as long as I have followed the game which dates back to 1958.

As a child growing up in the 50’s and 60’s , the frequent reference to football was “wogball”.

Unfortunately, the game faces a bigger threat in the 21st Century in the guise of the non football people who dominate the administration of our game and use it as a means for financial and personal gain.

One day I will write piece on this disturbing situation.

Incidentally, Mr Syson could you please in the future refer to our sport as football, not soccer, because it is the only true football code.

By calling it soccer, you are also supporting the cause of the anti football people like Kevin Sheedy.

Roger, what makes you think I am oblivious to the wogball prejudice? I think that nothing could be further from the truth.

No I will not stop using the word soccer. As a football historian I need to use it to distinguish between the codes. But I also believe that renaming the game football was an arbtirary decision made by a push within the game that was anti-ethnic, some of whom were the very “non football people” you criticise. You might be interested in my reasoning here: http://neososmos.blogspot.com.au/2012/08/why-i-still-call-game-soccer.html

Ian, thanks for replying. Your comment re the change to football by the FFA is interesting because I have used the term” football” since I started writing about the game in 1992.

I don’t necessarily agree about non football people being the force behind the anti -ethnic movement because they have purely an agenda which is designed to promote their positions as they have no real interest in the progress of football.

Furthermore, I’m not sure if you clearly understand the meaning of non-football people in this context.

Admittedly , David Hill , the former ASF chairman, did promote an Australianisation of the game in the early 90’s , particularly when he removed profitable clubs like, Melita Eagles ,from the NSL.

You have every right to call the game soccer but it will always be football for the majority of the world’s population.