My cousin is a great storyteller. I don’t mean good at making up stories, he’s just a good raconteur. In a very ‘old world’ quality, he describes every detail, puts things into context and order. For that, and others have confirmed it, I am assured the events of this story actually happened.

He, along with his family, lives in a small village in northern Bosnia. He is about 35, and along with his wife and two daughters, lives with his parents in their home. His younger brother and his wife and daughter, also live under the same roof.

In this part of the world, this is the norm. People don’t have much but they seem content. Aside from the latest high-tech gizmos, their existence has been fairly uniform for decades. Here, for the most part, each family harvests its own food, and the chickens roam free.

The house they live in is typical of the region: unrefined, made of red brick and seemingly always unfinished. Resting between this dwelling and the road is a much more humble and older dwelling, in which my 80-year-old grandfather lives alone. It’s basically a one-room cottage or bungalow with a veranda covering its entrance, where the old man routinely sits, eats, drinks slivovitz, smokes endless cigarettes and finds out what is happening via the daily rag or his trusted transistor – as is customary of old men, there. Where he lives now, my uncle and his family used to live, and where their new home is now, my grandparents’ home used to sit.

The family is well known in these parts, not because they are rich or powerful – they’re not – but because they’re considered regular, hardworking and decent people. My uncle is considered a great singer, which helps, but the family has for long been known as having good footballers in their midst. Although none of them had any big-time careers, quite a few of the family were – are – talented players.

In his youth, my old man was rated highly in the region but never went anywhere football-wise. Life always seemed to get in the way. Here, football’s more than just a pastime, it’s been a tradition for generations. The local club has the same surnames, year in year out, in its ranks. Like the village, the club is tiny and has two teams – when they can get everyone together.

Due to the events of recent decades and because of the dire economic situation, most people don’t have regular jobs. The local economy is based on favours and their returns. Football is the most acceptable vice, and becomes a thing one can do when he is not working to provide the basics. Therefore, games are often difficult to organise. The equipment on show is either borrowed or a well-worn hand-me-down. Like their lives, it’s practical and modest. If one had a choice, Adidas World Cups would be boots, and ‘the Tango’ the ball, of choice. Shin pads are as rare as the crowd. There’s the odd old man who comes to watch while his cow eats the grass that surrounds the ground. It’s a far cry from the Nou Camp or the San Siro, but for them this as good as it gets.

If they aren’t playing, like the rest of us, they are betting doodly-squat amounts on ridiculous odds in far away leagues and superior competitions.

The cousin of whom I speak of is a goalkeeper. He drives a truck for a living, and until recently was delivering furniture all over Europe yet hadn’t been paid a wage for years. As is often the case in these parts, the ‘employers’ claim not to be able to pay their staff; instead they give them the company’s wares that the employees then sell on to friends or family. When he has a spare moment, he craves to play with the rest of them.

During one of these matches earlier this year, he claims to have had a sudden urge to leave the ground and return home which is about a kilometre away. As it goes, those who were at the ground were saying to him: ‘What are you doing? Where are you going? We are playing… You’re our keeper! Are you alright?’ Unfazed, he supposedly turned away and nonchalantly left, saying he had to return home as if something was urgently calling him. Like a man possessed, he walked without stopping or slowing for a second. His catastrophising may have been associated with the fact his youngest daughter would’ve barely been one year old, and his older daughter – she’s around six – is often too bright and curious for her own good. Besides, people in these parts, while religious, are more superstitious and seldom resist any calling from ‘above’ and often look for deeper meanings in things.

As he entered his yard and turned past the cottage to walk towards his home, he claims to have seen something unusual in the corner of his vision. Amidst an opening within the small brick fence marking the cottage’s veranda boundary, he saw what looked like someone lying on the ground. At closer inspection, it was our grandfather. He wasn’t dead but was in obvious distress. Quickly observing that his grandfather was having a meal prior to his misfortune, he concluded that the old man must’ve been choking on something, as if his bulging eyes – by now the size of billiard balls – and his ballooning red face didn’t paint an accurate enough picture!

In an understandable panic, the cousin began demanding of the old man to tell him what was troubling him. Sitting over and beside him, the cousin began lifting him by his clothes, pushing on his chest, as the old man lay there helplessly twitching and fighting off a hidden demon. Both seemingly were close to the end of their wits. Sensing the level of desperation elevating as time and oxygen agonisingly passed, the cousin had to act to try and avert this catastrophe.

At first try, he claimed that the old man’s mouth was like a steel trap and he couldn’t open it. On the second attempt, he said he grabbed his grandfather’s chin across his jaw with one hand, and reached across his top lip and under his nose, with the other… He finally manages to force his jaw to open, upon which moment he claims to see the old man’s clear troubles: his tongue is not where it should be, but is folded and seemingly heading backwards. Holding his jawbone ajar with one hand, the cousin then attempts to poke inside the old man’s mouth with the other. The steel trap shuts, biting down on his fingers with great force. The cousin, through grimace and pain, clenches his teeth, twists his unseen fingers and with the other hand reaches again across the old man’s face in a last-ditched attempt to remedy the two’s predicament. This time around, success is rather more forthcoming; he manages to reopen his mouth, and forcing it to stay open this time, desperately hooks his fingers around the old man’s tongue, yanking out this vital yet grotesque muscle with all his might.

Almost instantly, the old man offers signs of relief, and within the same moment – the cousin swears by it – a projectile is shot out of the old man’s oesophagus as if out of a howitzer. It’s a ping-pong ball-sized chunk of meat, a morsel of pork – the essence of the region and its people – that is now in super-slow motion travelling through the air, like a mortar shell that scarred the flat landscape barely two decades ago. It is arcing on a trajectory from the old man, past the bemused cousin, and over the small bricked fence of the cottage veranda. As if it wasn’t enough of an occurrence by then, out of nowhere, the pork morsel is snatched from its descent by one of the passing chickens that roam freely in the yard. Followed by its flock, the chicken snaps up the morsel and runs for its life to indulge in this rarest of treats. And the cycle goes on: one being’s misfortune is another’s treasure.

At first, this obviously has nothing to do with Australian football, or Melbourne Heart. However, as I laid in bed last week anticipating Heart’s (another) “must win” encounter with the Wellington Phoenix, and thought about the stifling pressure put on the then-coach John Aloisi, his at-times lacklustre (and fanciful) story-telling, and his team’s ability to somehow always choke at the clutch moments, this family saga somehow mutated into the Heart saga.

Upon exploring the two side by side, I saw things in common. The Heart franchise, like a living organism fighting for its life, desperately sucking for air, to me, somehow fitted the role of my grandfather. My cousin, playing the role of saviour can be assumed by the Heart supporters who are so keen to resuscitate this (quickly) ageing and dying creature. And with them, perhaps the Australian football public – those cold-blooded schadenfreudians who revel at any blood spilt in the A-League circus yet deep down just want the best for the local game and hate dodgy appointments – which this obviously was.

That only leaves the pork morsel and the tongue, and who gets their starring roles. In this metaphor, I thought it’d be most appropriate to imagine the tongue as being poor-old JA – entrusted with a vitally important position, always trying to do the right thing; instinctual, and for better or worse can do or say anything; yet at times so proud and hard-headed and likely to get bitten. In this case, the tongue, like Aloisi, was holding the creature captive, preventing it from operating as it normally would or being able to continue the organism’s existence. It didn’t want to let go and in the end was wrenched away from the beast.

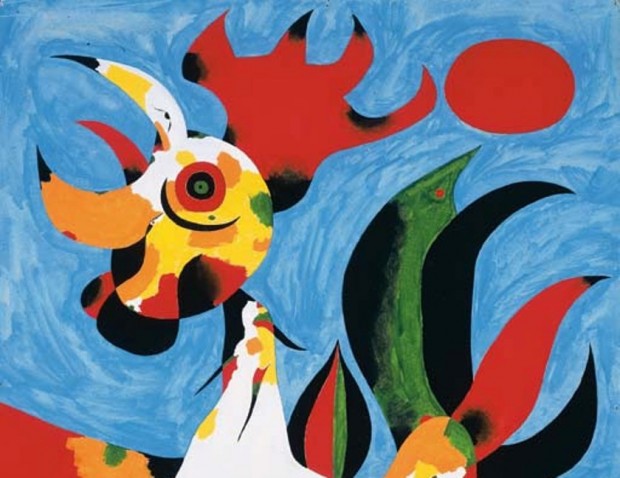

Naturally, that leaves the morsel to play the role of the Heart coaching job: tasty, rewarding, yet precarious, unpredictable, and if not chewed or digested properly can be more trouble than it’s worth. And so as it was propelled into the ether, it jumped into the flock of chickens who we can say represent that pool of hearty candidates for such coaching roles, and became just another coaching gig up for grabs. And in this case, snatching the bit and running with it, the rooster, the lucky bird, the most exotic chicken is a familiar one – John van ‘t Schip. And so it goes, the table of life keeps turning.