I can spot a Balkanite a mile away. Now, sure, this may not be a veritable life skill by any means, but I have a knack for seeing someone on the street and going, “Yep, thaaaat one’s from the old country.” There’s just something about the countenance, the visage. And last Melbourne Cup Eve it was easy because, well, they were all headed in the direction of Dudley Street. It was like shooting fish in a barrel.

My husband Igor and I approach the venue. There’s a throng of people, an all-too-familiar buzz. The heavy cigarette smoke alone would be a dead giveaway even under normal circumstances. A cacophony of former Yugoslavs milling about West Melbourne in the vicinity of a soon-to-be-packed-out Festival Hall. We’re all here, Serbs, Bosnians, Croats, Macedonians; the whole shebang. Hugs, back pats, grins, nods, whatsups, whatsnews, whereyabeens. Chain-smoking. There is a cross-section of people here, from all walks of life, and some of them are quite evidently (for lack of a better word) Balkan bogans.

Surreal doesn’t begin to describe this evening, I think. It’s terribly bizarre waiting to see in concert one of the defining bands of the Yugoslav music scene…and seeing them as part of a phoenix-like diasporic mass tens of thousands of kilometres away, on the other side of the planet, more than 25 years since the start of the war, the war that ultimately ended up being a slingshot to here.

“…and we’ll stand naked and alone beneath the frozen sky and dark…the scent of wormwood and empty fields abounds, roses in bloom and honey, but it could’ve been better.”

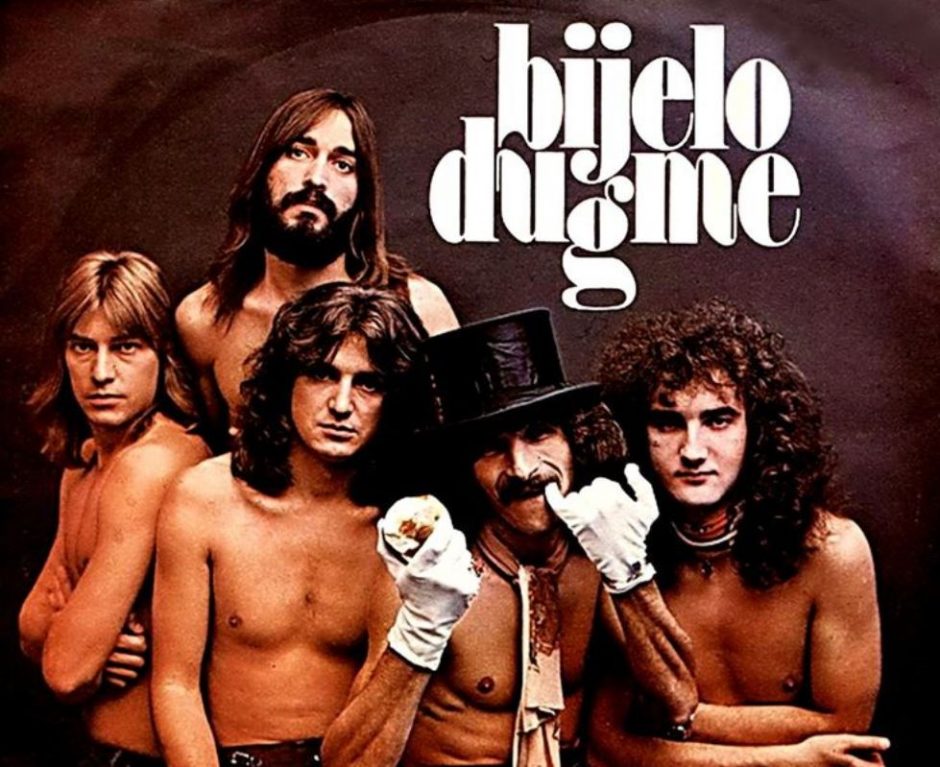

Bijelo Dugme (White Button) were a (mostly) beloved Yugoslav rock band, hailing from Sarajevo. They shot to fame in 1974 and captured the imagination with their Kad bi bio Bijelo Dugme album (If I Were a White Button); they disbanded in 1989, a year after the release of what would be their final album, Ćiribiribela. As time wore on, it seemed that Dugme (with founder and songwriter Goran Bregović “Brega” at the helm) was a band you either loved or loved to hate. Many mockingly referred to it as a newfangled genre of “shepherd rock”, and later in the 90s claimed that Bregović was to blame for ushering in an era of ethnic ululating turbo folk that would come to dominate in most former Yugoslav territories. Brega was a frontman who exuded a blend of smarts, charm and sleaze in almost equal measure. Bijelo Dugme had three singers: Željko Bebek (the original and longest serving), Mladen Vojičić “Tifa” and Alen Islamović. Some songs echoed or sounded akin to prolific bands of the West, such as Sve će to mila moja, Pjesma mom mlađem bratu, Šta bi dao[…], Sanjao sam noćas), while some were kitschy, infantile and tongue-in-cheek, for instance Da sam pekar, Hop cup, Hajdemo u planine. A number of songs were deliberately infused with sociopolitical imagery, highlighting the goings-on in the Yugoslav landscape and the nascent jingoism therein. In their fifteen years, Dugme had created a mythology of sorts.

According to Peter Liotta in his book Dismembering The State: The Death of Yugoslavia and Why it Matters:

[No band] was more important than the group Bijelo Dugme. No composer was more influential than its leader, Goran Bregović, the son of a “mixed” marriage of a Serb and Croat. [Bregović] equally realized how Bijelo Dugme, which came to be known as “the Beatles of Yugoslavia,” succeeded in actually Yugoslavizing rock music. Goran Bregović maintains that while the West, particularly bands such as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, had initial influence, the development of rock ‘n’ roll took on an identity that reflected the turbulent times and the turbulent spirit of Yugoslavia. For Bijelo Dugme, Bregović’s intent was to create a “Yugoslav character to our music . . . a bit too rude and too primitive for the outside world.”

Perhaps the most daring attempt on Bregović’s part to portray the zeitgeist of difference among Yugoslav peoples occurred as natural process of the evolution of Bijelo Dugme.

“[We] started with songs about love and now sing mostly about politics. […] You can see this even in music. Serbs and Croats have their own songs, which are more important for them than any “Yugoslav” songs. Last year [1988] I put together their two national hymns in a single song, and when I played this at some recent concerts, it resulted in small wars. The Croatian hymn “Lijepa nasa” [roughly, Our Beautiful Land] and the Serbian hymn “Tamo daleko” [There, Far Away] put these together under the title “Lijepa nasa.” Not to take sides, of course.”

The concert begins and people lose their minds. No surprises there. Bregović is here with Alen and Tifa (Bebek is MIA; apparently he and Brega had a falling out a few years ago), but also his Weddings and Funerals Orchestra. The songs whip people into a frenzy, and I’m not immune. I’ve always loved Bijelo Dugme. In one way, the glee feels more heightened purely due to the stark, sobering knowledge that many people here, myself included, experienced the 1990s war and the agony of that senseless hell. It’s like a spectre you can’t quite shake off, especially when confronted by songs laden with so much meaning, symbolism.

“Yugoslavia, on your feet, sing so they can hear you, whoever doesn’t listen to this song will hear a storm!”

The audience sings fortissimo in unison. I’ve always enjoyed Pljuni i zapjevaj moja Jugoslavijo; it’s brazen, brash, even musically ugly in parts. The irony of the tune is not lost on anyone here, though, I’m sure. A number of fans in the front row are brandishing the Yugoslav flag, a poignant symbol of (lost? regained? never-gone?) brotherhood and unity. It’s like an awkward afterthought, an exercise in futility in light of that horrific, pointless war and the divide et impera. I’m reminded of an acquaintance’s recent remark when he said, “All that needless, senseless bullshit, the division, the tragic bloodshed, but still we’re all together again here, at concerts, events, living together and loving each other in this city…we can’t escape one another, much as some chauvinist-nationalists may want to.” I caught the tail end of Yugoslavia’s existence, born in 1985. My parents neither indoctrinated me about Yugoslavism nor our Serbian heritage. I’m a pacifist and a Croatian Serb who’s also something of a Yugonostalgic.

Both Alen and Tifa are singing quite well, though I prefer Alen’s voice tonight – it’s uncharacteristically mellower while still strong, whereas Tifa’s is a little too caterwaul-y in parts. Bregović is standing at his mic, singing backing vocals, and playing the guitar a tad too stiltedly for my liking. When he sings certain solo bits, his voice is a weird raspy growl.

I’m torn on Bregović. I’ve always had a bit of a love-hate thing where he’s concerned. I’ve enjoyed a lot of his music, and twice attended his Weddings and Funerals Orchestra concerts in Melbourne where people were dancing in the aisles at Hamer Hall[!] because of the dizzying highs the music incites. After the second show I decided I was done – I’d had more than enough of his white-suit-adorned self half-assedly playing the guitar while sitting down, flanked by the orchestra, and doing a poor, laughable imitation of a conductor while, in one instance, raising his index finger up and down to the male octet in his orchestra. There are hits and misses. There are songs he’s plagiarised. His disposition is lackadaisical and he looks stoned half the time. Let’s not forget his shit-eating grin. (I’ve eyerolled about that many a time to my Igor; it’s like he’s a smug businessman.) (Well, come to think of it…) But I have begrudging respect for Brega nonetheless. There are a fair few songs of his I, quite frankly, loathe. (Balkañeros and Manijaci, anyone? Shudder. Quelle horreur.) And yet, I don’t loathe him. He created an anthology of important songs in people’s lives through the Dugme phenomenon. He’s the soundtrack to people’s pre- and post-war experience. He’s broken through, he’s internationally known.

And so, although tonight is a little too Bijelo Dugme 2: Electric Boogaloo, what with Bregović’s orchestra in the house, I can’t quite hate on it. I don’t hate it; far from it. I still can’t help loving a lot of these songs. The fact is, many are genuinely great. My friends and I dance up a storm to them, scream-singing the lyrics at the stage, feeling a sense of exhilaration at the primal, rootsy, toe-curling sounds of the horns, the Balkan brass. The band takes you to church. It’s euphoric, it’s melancholy, special.

Because here’s the thing: these songs saw people through first longing looks, open-mouthed kisses, first loves, heartaches, momentous festivities, farewells, the tapestry of friendship, and, yes, through(out) that bullshit, unnecessary war, too.

There are many reasons why I shouldn’t care, or why I should roll my eyes or be dismissive. And yet, I can’t quite find it in me to do so. In spite of the admitted negatives, I can’t find it in me to scoff at this, to belittle or diminish, look down my nose at it. Perhaps it’s the significance and ubiquity of Dugme’s music since I was born, or perhaps it’s just me.

“They ask me about you, but I keep quiet, I wonder which hip you sleep on, do you wake […] a white dress for New Year’s, and you’re leaving with him […] oh if only I didn’t love you.”

It’s 1990/91, and we’re at our neighbours’ place just across the hall. We’re all watching the satirical (and ultimately prophetic) sketches of Top Lista Nadrealista, Yugoslavia’s version of Monty Python. Laughter rings out, stunned cackles. We’re kids and we don’t get it, but we mimic the parentals’ laughter. They smoke and swig beer, rakija, throwing back crackers, prosciutto and cheese. “Jesus, no way there’s gonna be war,” they say, while puffing on their many cigarettes in the coiling grayish plume of the lounge room. “I mean, are they mad? War? No one is that insane to allow it to happen.” Later on, the radio plays, amongst other things, Bijelo Dugme. Of course it does, it always did. Ad nauseam, even.

“I’ll never return to my hometown, no one waits for me there, all faces have long ago faded, and I long ago forgot their names…”

We were also in Sydney during that Melbourne Cup weekend, Igor did the Sydney to Wollongong charity bike ride for MS, and just before roadtripping back home for the concert, we visited a restaurant in Cronulla. Our waitress had that face, a face that looked uncannily like she could be of Slavic heritage. She was girl-next-door beautiful; dark chestnut hair, striking blue eyes. “She looks like she could be from Southeastern Europe; I bet she is,” I mumble. When she returned, me being me I asked “Hey, do you mind my asking where your accent is from?” She smiled and replied, “Slovakia.” We knew she was of Slavic background, we tell her. Bratislava, we ask? No, she’s from a small Slovak village, Krasno, she tells us. We establish that krasno means beautiful in both Serbo-Croatian and Slovak. She mentions how some people say she’s from Czechoslovakia and she laughs and tells these geographical ignoramuses that, hey, it hasn’t existed for many years. “Well, at least you guys disintegrated peacefully, unlike us,” I find myself telling her.

“Dreams are pressing down, sticky and strong, is death sleeping at this ungodly hour?”

My eyes keep darting back to Bregović. I wonder whether he knows he’s on virtually sacred ground, that his heroes The Beatles performed in this very hall in 1964 and he’s standing where once they stood. My eyes spring with tears at a few particularly emotional Dugme songs and I think about the poignancy of this night, after everything, after ends and beginnings, prodigious resurrections. Dugme were one of my late dad’s favourite bands. I wonder what it would be like if he were here with us, whether he’d enjoy or whether a hefty dose of cynicism would have crept in by that point.

I look at Alen, Tifa, and back again at Brega. He’s an annoying, frenetic blend of good and bad, of shrewdness, passion, lethargy, smarts, cunning, laziness, heart, bravado, braggadocio, defiance, hope and candour.

And maybe, in all of that, is the beauty and the curse of our once and former home region.

Maybe that’s why we want to spit at it, akin to scorned lovers; why we love and loathe this spectacle in equal measure.

Maybe that’s why nights like these still ache, just a smidge.